Decoding Palms: Deciphering Plant Mysteries One Publication at a Time

When you think of Los Angeles, there are some iconic things that come to mind: the Hollywood Sign, the Santa Monica pier, the Hollywood Walk of Fame — and palm trees. Call up a photo of Los Angeles’ cityscape, and chances are you’ll see palm trees. They are ubiquitous throughout the city, growing along major boulevards and picturesque residential streets, populating parks and framing beachside boardwalks.

While today it’s hard to conjure up imagery of Los Angeles without these towering plants, that was not always in the case. Before the end of the 19th century, Los Angeles was a scrubland desert, no palms in sight. As developers moved into the area in the late 1800s, they wanted to find a way to make the desert more appealing. Palm trees, with their tropical and exotic associations, were just the ticket, especially since they are relatively easy to transport (they have a small, dense root ball rather than elaborate root systems) and thrive so long as they have sun and water.

Developers planted them everywhere, and they became a staple of Southern California [1].

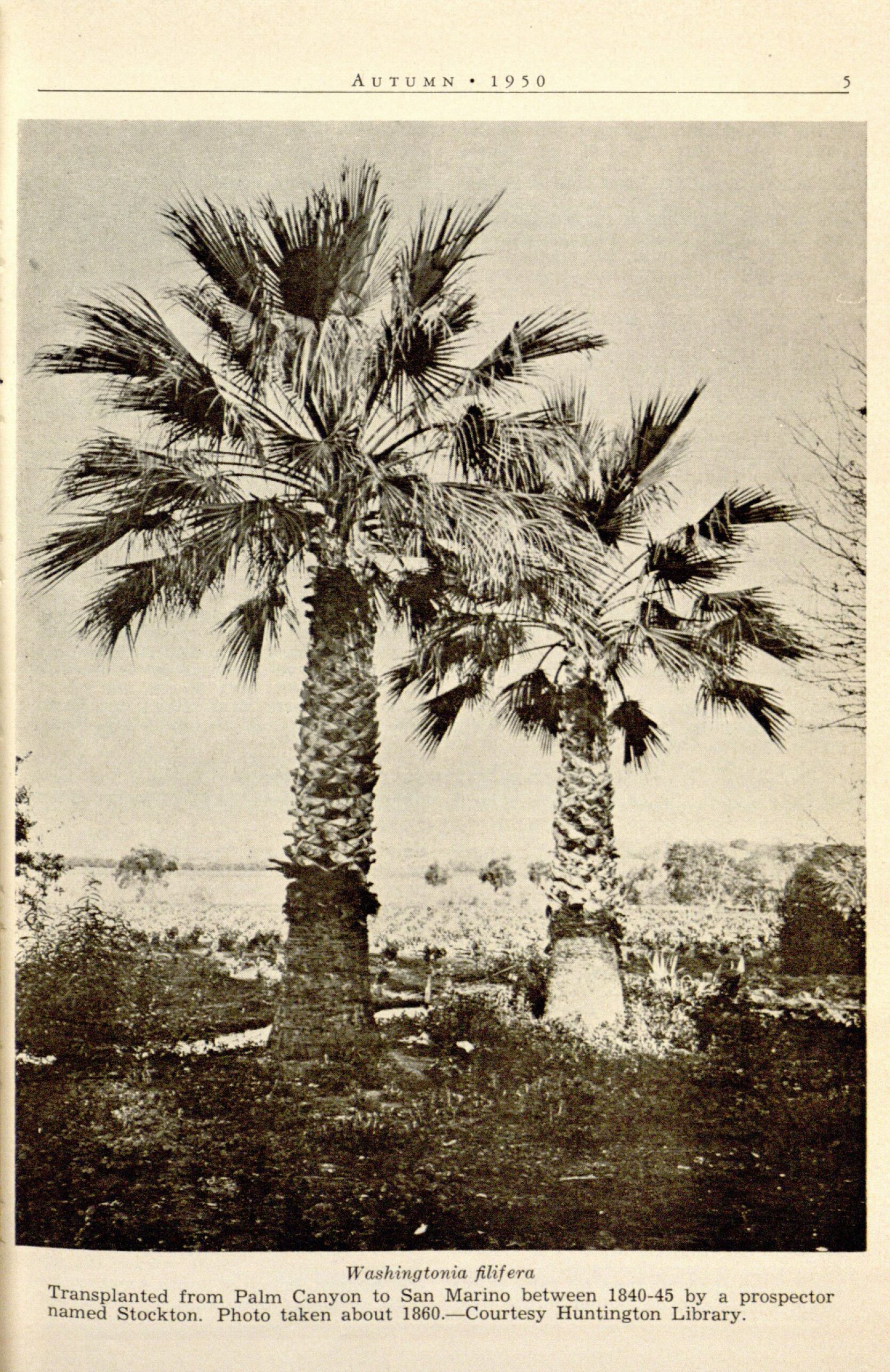

California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera) transplanted from Palm Canyon (outside Palm Springs, California) to San Marino (Los Angeles County, California). Hertrich, William. “Washingtonia filifera”. Lasca Leaves, 1:1 (1950). Contributed in BHL from the Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library with permission from The Arboretum Library at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden. CC-BY-NC-SA.

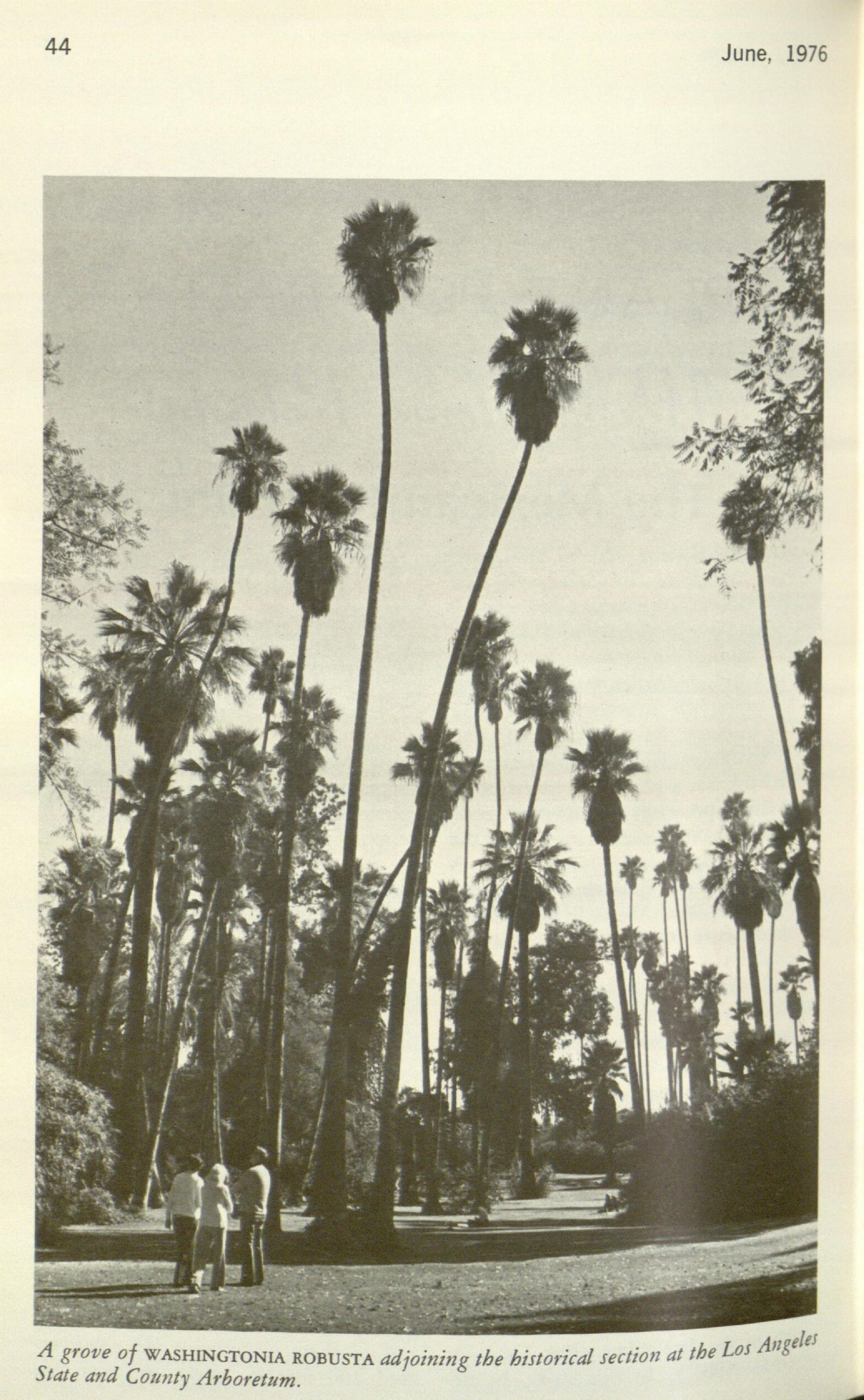

Given their strong association with the area, you might be surprised to learn that there is only one species of palm native to the entire state of California — the California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera), native to the southwestern United States and northwest Mexico. It is one of two recognized species in the genus Washingtonia, the other being the Mexican fan palm (Washingtonia robusta), native to western Sonora and Baja California Sur in northwestern Mexico. Both are among the palm tree species found in L.A., with the Mexican fan palm in particular reaching exceptional heights throughout the city.

A grove of Mexican fan palms (Washingtonia robusta) “adjoining the historical section at the Los Angeles State and County Arboretum.” Deardorff, David. “Washingtonia Robusta: the Mexican fan palm.” Lasca Leaves, 26:2 (1976). Contributed in BHL from the Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library with permission from The Arboretum Library at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden. CC-BY-NC-SA.

Dr. Lorena Villanueva-Almanza, outreach coordinator at the California Botanical Society, specializes in the Washingtonia genus. As a plant taxonomist, her work focuses on understanding plant relationships and the many ways and names under which plants have been described across time — something she is currently engaged in for the Washingtonia. BHL is an invaluable resource for this work.

“Sometimes, the same plant will have multiple names, something we know as a synonym. In order to clear the confusion, I must look for the original publications — the protologues — in which they were first described,” explains Villanueva-Almanza. “The protologue gives me information about when a taxon was first published, traits that can help me determine the plants that I am working on, and if any type specimens were designated. BHL is a great resource for finding these protologues and, ideally, a solution to taxonomic and nomenclatural problems.”

Dr. Lorena Villanueva-Almanza after arriving at her lab from a trip to the Baja Peninsula. Photo Credit: Javier Sabines.

Villanueva-Almanza has been studying plant taxonomy and systematics for twelve years. She first discovered BHL in 2011, while working as a research assistant for the Flora of the Tehuacán Valley Flora project in Mexico City. Since then, she has used the Library for all of her nomenclatural research. She refers to it daily in her work to identify Washingtonia synonyms and trace type specimens, downloading relevant pages as well as images of possible types in cases where these might be illustrations rather than herbarium specimens.

Villanueva-Almanza cutting a leaf from a Brahea armata palm at Cañón Berrendo, Northern Baja Peninsula. Photo Credit. Javier Sabines.

Being a plant taxonomist is rather like being a detective, explains Villanueva-Almanza. Working out the often convoluted taxonomic history of a species or genus means digging into historic texts and protologues and piecing together information across multiple centuries and languages. BHL makes it easy for her to locate relevant information with its full text “search inside” functionality and author searches that often lead to new publication sources.

“BHL provides invaluable material that sparks my detective skills,” attests Villanueva-Almanza. “It does a great job cross-linking data. I have found more information than I was originally looking for, allowing me to piece together the botanical history of Washingtonia palms with newly discovered information.”

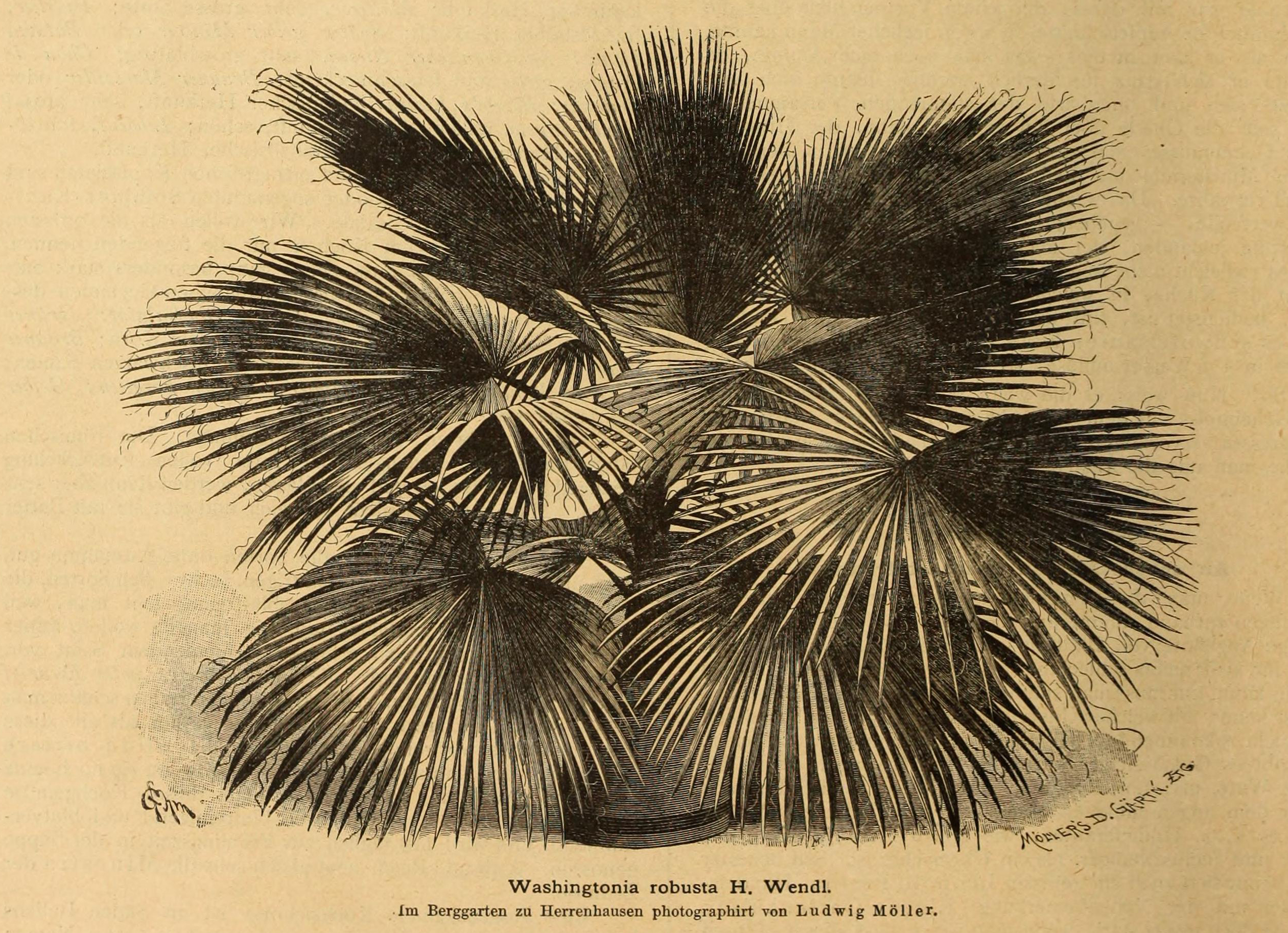

One such example of the kind of unexpected discovery made possible thanks to BHL relates to the original collecting location for the Mexican fan palm (Washingtonia robusta). While taxonomists knew that W. robusta was described from a cultivated palm, it has long been accepted that it was first collected in Baja California Sur. However, after studying a passage published in Möllers deutsche gärtner-zeitung(1888) in which Hermann Wendland — the author of W. robusta’s original species description — discussed the specimen that was sent to him by Louis van Houtte in the spring of 1883 for identification, and upon which his description was based, Villanueva-Almanza realized that this assumption was baseless.

“I remember the awe I felt when I read, translated, and finally realized the importance of Wendland’s notes on W. robusta,” recalls Villanueva-Almanza. “Wendland admits that he does not know where the specimen was collected, which means we do not know its original location. I knew that what I had found would change the way we had interpreted the genus Washingtonia.”

Illustration of Washingtonia robusta published along with Hermann Wendland’s 1888 passage discussing the original specimen sent to him for determination, and upon which the original species description was based. Wendland, Hermann. “Washingtonia robusta H. Wendl.” Möllers Deutsche Gärtner-Zeitung, v. 3 (1888). Contributed in BHL from University Library, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.

While unraveling taxonomic mysteries may sometimes simply lead to more mysteries, Villanueva-Almanza is up to the challenge. By providing easy access to historic texts through a single, convenient online portal, BHL allows her to make discoveries that eluded researchers of the past who may not have had access to such a breadth of material.

“Sometimes, finding a solution becomes a bigger challenge than I anticipated. However, I am particularly drawn to old mysteries,” affirms Villanueva-Almanza. “BHL has been a crucial part of my research — first, by acknowledging the value of historical publications and second, by making them accessible.”

View of Palm Canyon, where Villanueva-Almanza conducted her fieldwork for her dissertation on Washingtonia palms. Photo Credit. Marta Ruiz.

We’re proud to know that BHL is living up to its vision of “Inspiring discovery through free access to biodiversity knowledge.” And while the original collecting location for Washingtonia robusta may still be a mystery, there’s no mystery about where you’re sure to see a Mexican fan palm today — towering over the streets of Los Angeles.

Leave a Comment