Hispanic Heritage Month: What is a Cordillera?

cordiller (cor·dil·le·ra); a noun.

Definition of cordillera : a system or group of parallel mountain ranges together with the intervening plateaus and other features, especially in the Andes or the Rockies.

Origin: early 18th century: from Spanish, from cordilla, diminutive of cuerda ‘cord’, from Latin chorda (see cord). (Oxford English Dictionary)

———————–

|

| Cordilleras! |

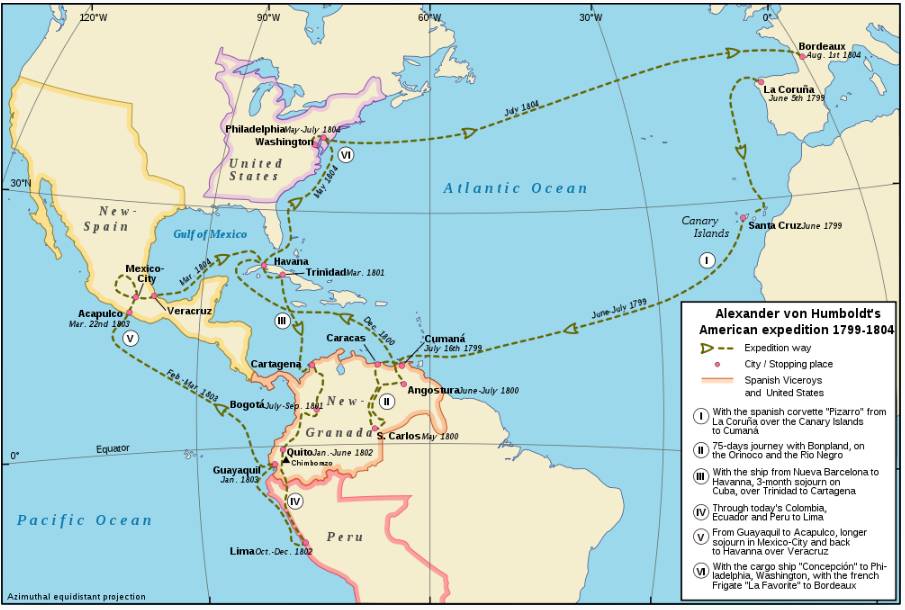

We saved something special for you for our final Hispanic Heritage Month blog installment. Today, we would like to bring your attention specifically to two Cordilleras found in Ecuador: the Cordillera Occidental and Cordillera Oriental which were extensively investigated by Alexander von Humboldt on his six-year expedition through Meso and South America. In this week’s Book of the Week, Humboldt provides us with the very first eye-witness account of some of the highest peaks found in the Andes and minutely describes their geology in: “Researches concerning the institutions & monuments of the ancient inhabitants of America : with descriptions & views of some of the most striking scenes in the Cordilleras!” Despite the long title, this two volume tome is actually just an excerpt from Humboldt’s much more voluminous 30 volume work, Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent that he produced after his expedition.

|

| Routing Humboldt and Bonpland’s S. America Expedition |

|

| A young Humboldt |

Having the fortune of receiving a substantial inheritance following the sad event of his mother’s death, Humboldt quickly opted for a career change. Seemingly overnight, he leapt from Government Mines Inspector to Greatest Explorer the World had ever seen! Leaving the Old World behind for the very first time, he was accompanied Aimé Bonpland, a botanist who over the course of the next six years, from 1799-1805, would collect over 60,000 plants on their expedition to a largely unobserved continent and the species that they brought back were mostly unknown to Europe at the time. While Aimé focused on his field of expertise, Alexander preferred to dabble. Remembered as one of the last great scientific generalists, he believed “that no organism or phenomenon could be fully understood in isolation. Living things, the objects of biological study, had to be considered in conjunction with data from other fields of research such as meteorology and geology.” Therefore, Humboldt bounces along through his text touching on a myriad of topics, admitting no attempt at organization in his book. And remarkably the lack of organization and vacillations between linguistics, mythology, botany, oceanography, archeology, climatology and comparative religion all somehow come together. However, it should be noted that as much as Humboldt meanders about in this week’s book of the week he always comes back to his most beloved subject– geology. At the time, geology was an emerging field of science and he should be remembered as a primary contributor to its development into a modern field of study.

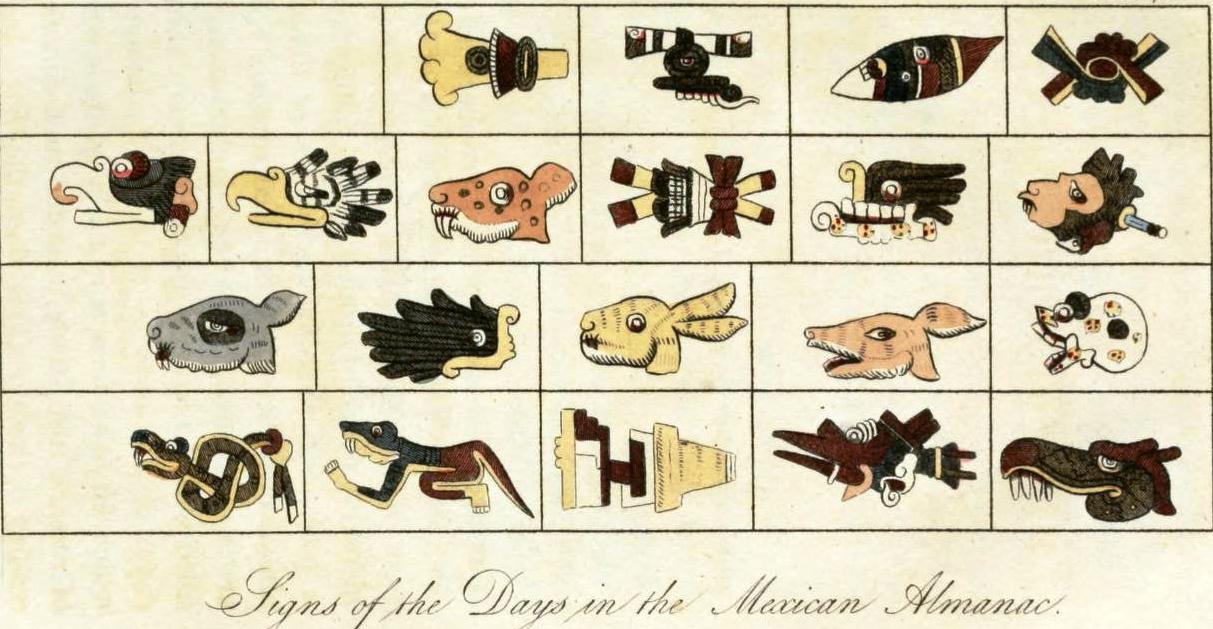

Throughout what might be best called a travel narrative or informal conversation with the reader, written largely in first person, Humboldt conducts a comparative analysis on his eclectic mix of chosen topics. He seems to be in constant search for the connecting thread that will illuminate an underlying unity in nature. While some critics find this propensity for long-winded unification theories unscientific, one must remember that during the backdrop of the time providing analogues to known phenomena would certainly help the reader to better understand the natural phenomena in this new and largely undiscovered world. Such is the case with these hieroglyphic paintings which Humboldt provides the reader a lengthy analysis, a treatise almost, on comparative mythology and linguistics:

|

| Fig. 1: Days in the Mexican Almanac |

|

| Fig 2: The Epochs of Nature According to Aztec Mythology |

Humboldt compares these paintings with the writing systems of the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Hebrews and many other ancient languages. Of the content in fig 2., he compares the epochs of natural destructive cycles in Aztec mythology with the notions of a Kalpa and Yuga found in Hinduism which are described at length here. A seriously fascinating read! The Aztec culture was clearly one very imbued with the sanctity of nature. These were a people who were impatiently awaiting the return of their god Quetzalcoatl because he brought with him a time in which “all animals, and even men, lived in peace; the earth brought forth, without culture, the most fruitful harvests ; and the air was filled with a multitude of birds, which were admired for their song, and the beauty of their plumage.” One might see why Montezuma would easily mistake Cortez for Quetzalcoatl. It was simply a case of wishful thinking.

Moving on to the crux of this book, interested in reading some of the very first observances of the best known peaks in the Andes? Humboldt delivers:

The Two Mightiest Peaks of Humboldt’s Cordilleras! Okay Three?

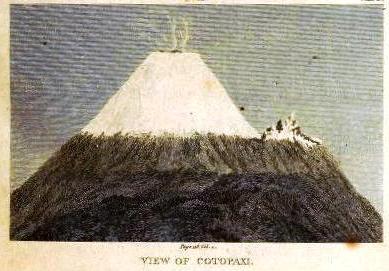

Volcano of Cotopaxi: This volcano towers at 19,347 feet. Since 1738, Cotopaxi has erupted more than 50 times. It is the second most active volcano in the world. Humboldt, the first European to climb Cotopaxi is lucky to have observed it and lived to tell the tale and he seemed to be clearly aware of this fact for, at the time of this sketching of Cotopaxi, Humboldt wrote this: “The colossal volcano of Cotopaxi, the pyramidal peaks of Ilinissa, and the Nevado de Quelendanna, open here at once on the spectator, and in dreadful proximity. This is one of the most majestic and most awful views I ever beheld in either hemisphere.”

Volcano of Cotopaxi: This volcano towers at 19,347 feet. Since 1738, Cotopaxi has erupted more than 50 times. It is the second most active volcano in the world. Humboldt, the first European to climb Cotopaxi is lucky to have observed it and lived to tell the tale and he seemed to be clearly aware of this fact for, at the time of this sketching of Cotopaxi, Humboldt wrote this: “The colossal volcano of Cotopaxi, the pyramidal peaks of Ilinissa, and the Nevado de Quelendanna, open here at once on the spectator, and in dreadful proximity. This is one of the most majestic and most awful views I ever beheld in either hemisphere.”

Pyramid of Cholula: Not necessarily a natural “peak” per se, the pyramid that sits at the site of the holy city of Cholula is home to the greatest, most ancient monuments of the Aztec people. The pyramid is referred to by locals as the mountain made by the hand of man (monte hecho a manos). From a distance it looks like a natural hill covered with vegetation. One can see why Humboldt would be intrigued.

Pyramid of Cholula: Not necessarily a natural “peak” per se, the pyramid that sits at the site of the holy city of Cholula is home to the greatest, most ancient monuments of the Aztec people. The pyramid is referred to by locals as the mountain made by the hand of man (monte hecho a manos). From a distance it looks like a natural hill covered with vegetation. One can see why Humboldt would be intrigued.

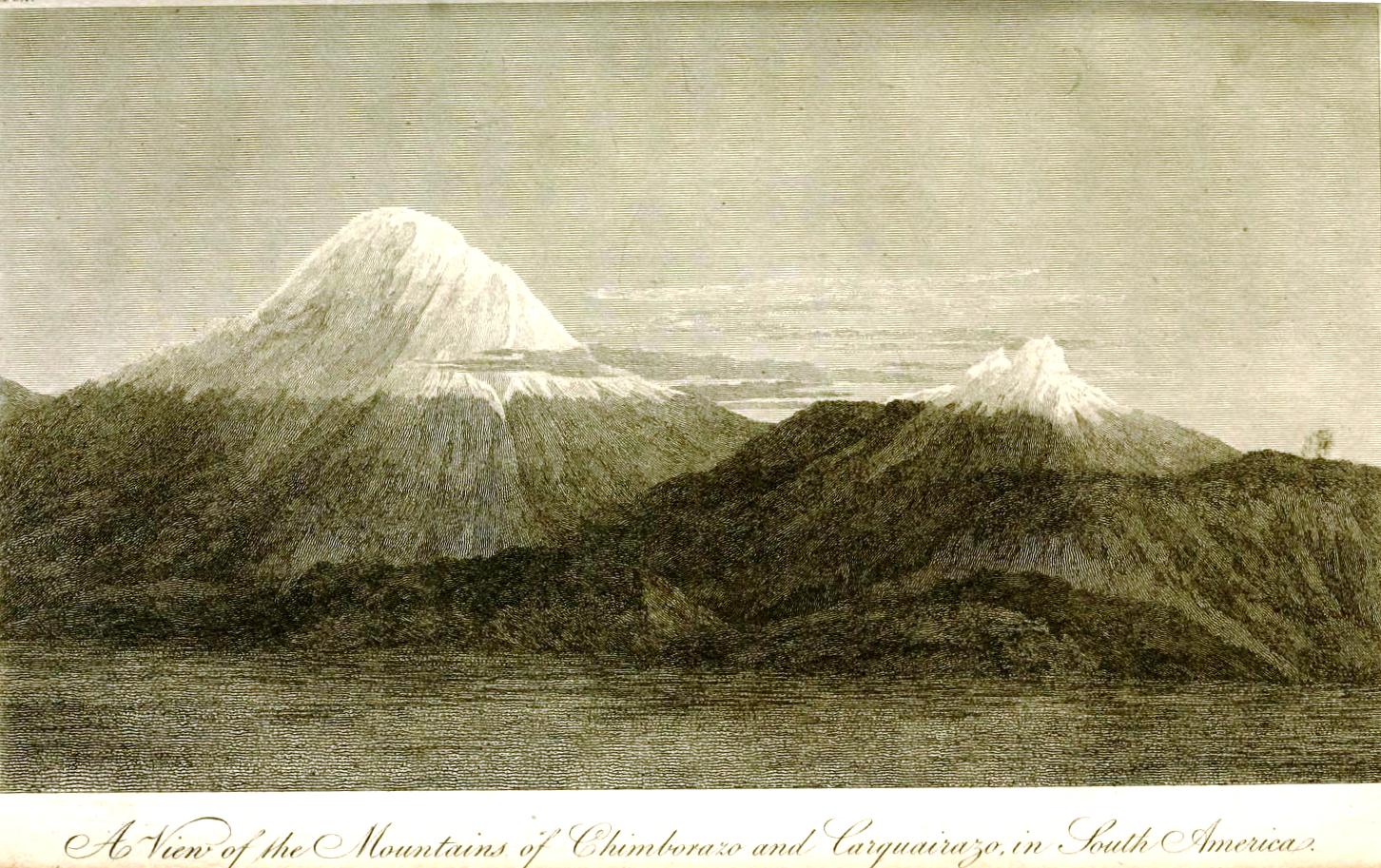

Mount Chimborazo: At 20,564 ft, Chimborazo is the highest mountain in Ecuador, the highest peak in close proximity to the equator and it is the furthest point from the Earth’s center. (This is due to the oblate spheroid shape of the Earth.) Bonpland and Humboldt attempted to reach the peak of Chimborazo but, did not reach the summit. Atop Chimborazo sits a layer of permafrost which adds to its majestic beauty. Spotting the behemoth in the distance, Humboldt writes “we see Chimborazo appear like a cloud at the horizon; it detaches itself from the neighbouring summits, and towers over the whole chain of the Andes, like that majestic dome, produced by the genius of Michael Angelo, over the antique monuments, which surround the Capitol.”

Mount Chimborazo: At 20,564 ft, Chimborazo is the highest mountain in Ecuador, the highest peak in close proximity to the equator and it is the furthest point from the Earth’s center. (This is due to the oblate spheroid shape of the Earth.) Bonpland and Humboldt attempted to reach the peak of Chimborazo but, did not reach the summit. Atop Chimborazo sits a layer of permafrost which adds to its majestic beauty. Spotting the behemoth in the distance, Humboldt writes “we see Chimborazo appear like a cloud at the horizon; it detaches itself from the neighbouring summits, and towers over the whole chain of the Andes, like that majestic dome, produced by the genius of Michael Angelo, over the antique monuments, which surround the Capitol.”

The wealth of knowledge, historical importance, and richness of travel description in this book should not be overlooked. Everyone with any curiosity about our natural world should read Humboldt. Geologists especially, should not miss today’s book of the week. It’s a true gem.

All these magnificent plates from Humboldt’s expedition are available on Flickr, plus more. Also,make sure to check the Twitter, Facebook and Flickr for more content celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month!

We hope you enjoyed this post. Interested in guest-blogging for BHL? We’d love that! Natural history, biodiversity and conservation topics are especially welcomed. Email us your ideas at feedback@biodiversitylibrary.org.

Leave a Comment