Fact or Fiction? Discovering the Mosasaur

If you’ve seen Jurassic World (or even just the trailers), then you’re familiar with Mosasaurus. In the film, it’s portrayed as a giant aquatic lizard thundering out of the water to devour great white sharks…and other mega prey.

Of course, the Jurassic World version is an exaggeration of the real thing (the film version is portrayed at 60 feet long, while the real animal maxed out at 46-50 feet long and was not capable of the water acrobatics depicted in the movie), but it is nevertheless based on a real, extinct aquatic reptile.

An historic account of an early discovery of mosasaur fossils is also probably more of an exaggeration than reality.

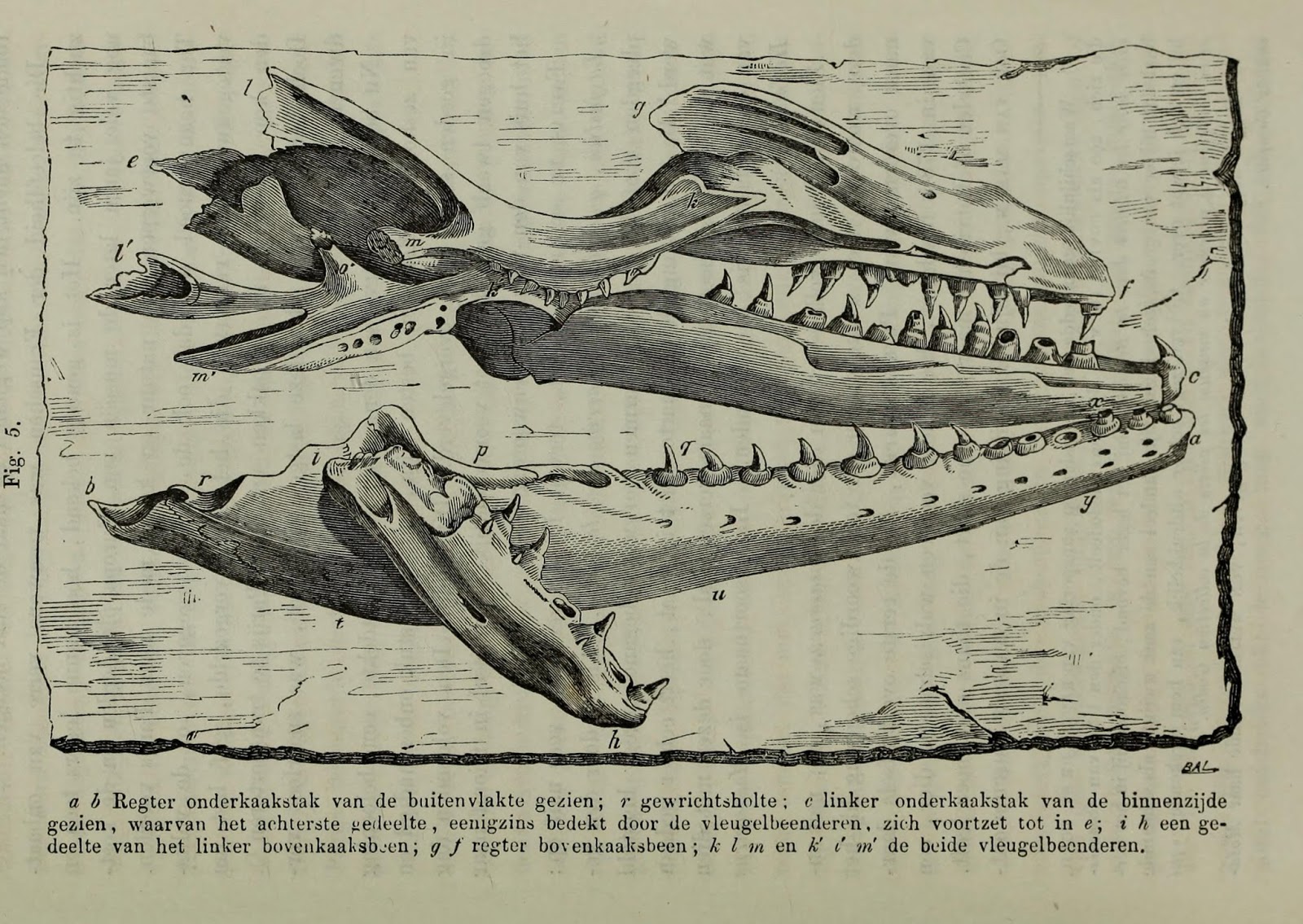

|

| Jaws of the Mosasaur. Harting, Pieter. Album der Natuur. 1866. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/35222337. Digitized by Natural History Museum, London. |

According to French geologist Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond’s eighteenth century account of the discovery of the second known partial mosasaurus skull, quarrymen at the subterraneous quarries of St. Peter’s Mount, at Maestricht, Netherlands, uncovered the massive skull embedded in the rock sometime between 1770-74. They informed local surgeon, Leonard Hoffmann, who reportedly offered a reward for any fossils discovered in the quarry. Hoffmann took the specimen home, only to have canon Godding of Maestricht, who owned the quarry, demand to have the specimen given to him, claiming rightful ownership since the fossil had been discovered on his land. Godding subsequently filed a lawsuit against Dr. Hoffmann, eventually gaining custody of the piece.

But the story doesn’t end there. In 1795, the French revolutionary army captured Maastricht. De Saint-Fond was the Scientific Commissioner for the army, and he entered Maestricht with the express purpose of securing the “celebrated head” for the French. However, when he arrived at Godding’s mansion, the skull had already been removed from the house. A reward of six hundred bottles of good wine was offered to anyone who could locate the skull and return it to de Saint-Fond. The next morning, twelve grenadiers brought it to the French camp, where it was packaged and sent to the Museum of Natural History in Paris. De Saint-Fond also reportedly offered a substantial renumeration to Godding for the loss of the fossil.

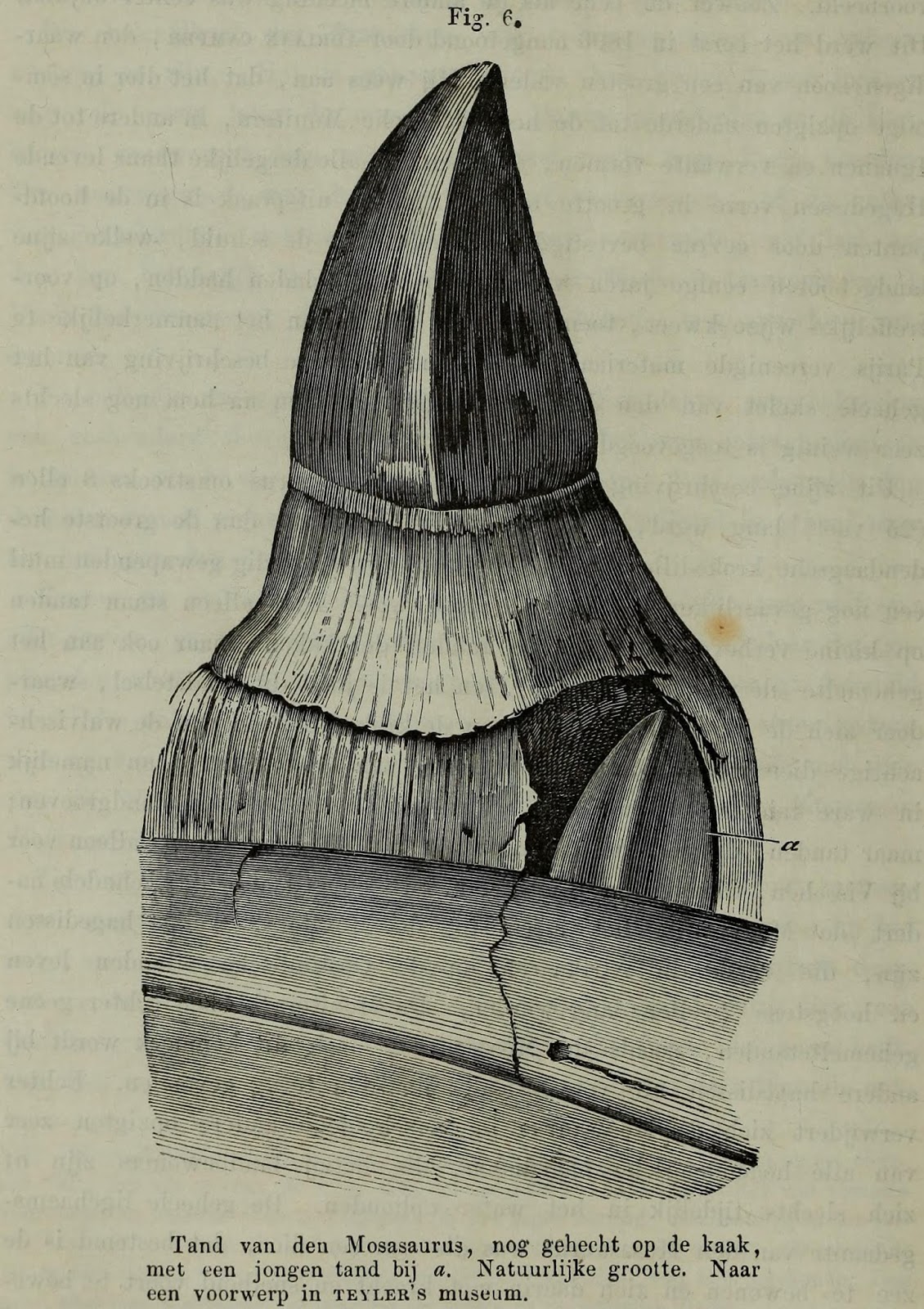

|

| Tooth of Mosasaur. Harting, Pieter. Album der Natuur. 1866. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/35222340. Digitized by Natural History Museum, London. |

And so the story goes. Dutch historian Peggy Rompen, however, has found the story to be more fiction than truth. According to her 1995 thesis, Godding was in fact the original owner of the skull. Hoffmann never possessed it, there was never a lawsuit between Godding and Hoffmann, and De Saint-Fond apparently offered no renumeration to Godding for the loss of the fossil. It seems that De Saint-Fond fabricated the story to justify the French seizure of the specimen.

|

| Mosasaur vertebrae. Camper, Adriaan Gilles. Annales du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle. v. 19 (1812). http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/3499442. Digitized by Natural History Museum, London. |

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the truth about early discoveries of mosasaur fossils (and additional evidence that some early fossils may have been tampered with), Leonard Hoffmann did corresponded with Dutch Professor Petrus Camper about the infamous mosasaur skull. Hoffmann believed the skull belonged to a giant crocodile, while Camper insisted it was some unknown toothed whale. In 1798, Petrus’ son, Adriaan Gilles Camper, reexamined his father’s description and decided that the skull must belong to a giant, extinct monitor lizard. He communicated this belief to Georges Cuvier in 1799, and in 1808, Cuvier indicated that, based on comparative anatomy, the specimen did indeed show affinities with lizards. In 1812, Camper published a longer description of several mosasaur fossils from Maastricht. Finally, in 1822, William Daniel Conybeare gave the animal the genus name Mosasaurus, and in 1829, Gideon Mantell supplied the specific epithet hoffmannii.

Fossil Stories

Stay tuned all week for more great fossil fun with our #FossilStories campaign, including:

- Tweets and Facebook Posts

- Blog Posts highlighting milestones and key publications in the history of fossil research

- A Flickr Collection with hundreds of historic fossil illustrations

- A Pinterest Collection featuring a selection of our favorite fossil illustrations

- A BHL Collection containing seminal publications in the history of paleontology

- A series of live webcasts at BHL partner institutions

- A citizen science challenge in collaboration with The Field Book Project, the Smithsonian Transcription Center, and Smithsonian Institution Archives

Leave a Comment