The Sea Dog: Exploring the Discovery & Classification of the Shark

It’s that time of year again! That special week set aside to celebrate the fabulously diverse Selachimorpha clade: Shark Week!

If you were to ask an average person to differentiate between a tiger shark, Great White, whale shark, bull shark, or mako, most could probably do so, or would at least be aware that such varieties existed. This wasn’t always the case. A mere six hundred years ago, sharks were known only by the bizarre personas recounted by animated sailors. And even when more accurate depictions and accounts began to circulate, the world was completely ignorant of the vast diversity of these creatures. A shark, generally, was a shark. It took an army of people, and several hundred years, to even begin to comprehend these magnificent fish, and we’ve still only scraped the surface.

The Shark in Myth

|

| A selection of monsters that supposedly plagued the Atlantic Ocean. By Abraham Ortelius. 1570. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. |

Eleven hundred years ago, man was just starting to venture boldly into the open oceans. At that time, and throughout the Middle Ages, the sea was a place of mysticism and superstition, with countless tales of leviathans, monsters, and spirits plaguing the waters. Researchers believe many of these tales were actually based on real creatures, however exaggerated. Some of the beasts may have been at least partially informed by shark sightings.

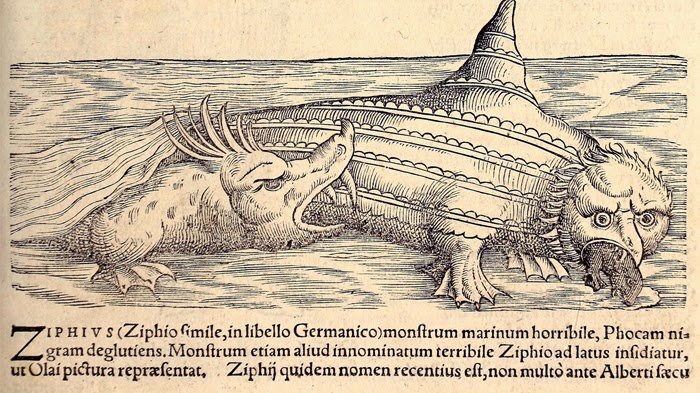

Conrad Gessner (the man behind our strange walrus a few weeks ago) depicted the Ziphius in his 1560 work Icones Animalium. Many researchers believe the beast with the back fin may be a Great White, due in part to the unfortunate seal in its jaws. The porcupine-fish taking a bite out of the Ziphius’ side? The jury’s still out on that one…

|

| The Ziphius. Conrad Gessner. 1560. Icones Animalium. |

Caspar Schott’s 1662 beast is equally fanciful, but the teeth and jaws suggest that it may be inspired in part by a shark.

|

| A shark? Caspar Schott. 1662. Physica Curiosa. |

Despite limited contact with sharks, or perhaps because of it, artists generally portrayed the fish as ravenous man-eaters. Olaus Magnus’ 1539 Carta Marina shows a hapless man besieged by a gang of sharks. Fortunately for him, a kind-hearted ray-like creature has come to the rescue.

|

| Olaus Magnus. 1539. Carta Marina. |

Also in the Middle Ages, fossilized shark teeth were identified as petrified dragon tongues, called glossopetrae. If ground into a powder and consumed, these were said to be an antidote for a variety of poisons.

The Shark as a Sea Dog

By the time of the Renaissance, the existence of sharks was more generally known, though their diversity was woefully underestimated. Only those species that were clearly distinct based on color, size, and shape – such as hammerheads, blue sharks, and smaller sharks such as dogfish – were distinguished. As for the Lamnidae – Great Whites, makos, and porbeagles – these were identified as a single species.

In the 1550s, we see the Great White debut to an audience that would remain captivated by it for hundreds of years, though under a rather strange monicker.

In 1553, Pierre Belon, a French naturalist, published De aquatilibus duo, cum eiconibus ad vivam ipsorum effigiem quoad ejus fieri potuit, ad amplissimum cardinalem Castilioneum. Belon attempted the first comparative analysis of sharks, and presented 110 species of fish in a much more realistic light than previously provided. In addition to a hammerhead, Belon included a woodcut of a shark he named Canis carcharias.

|

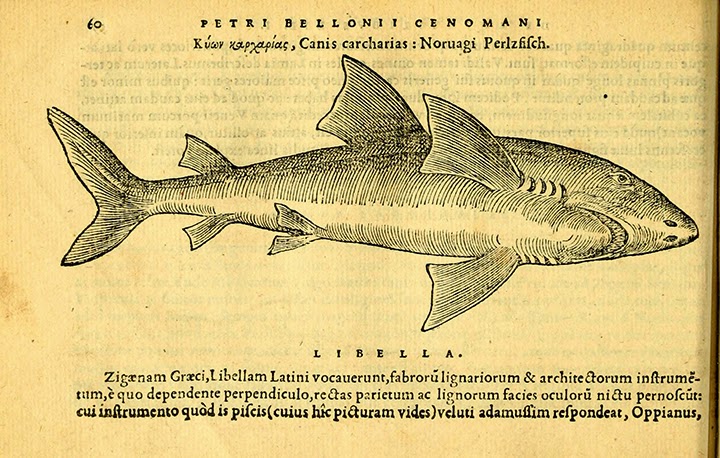

| Canis carcharias. Pierre Belon. 1553. De aquatilibus duo. |

Some readers may recognize that “Canis” is the genus currently assigned to dogs. Belon was not attempting to classify sharks with dogs by asserting this name. Indeed, systematic classification based on ranked hierarchies would not come onto the scene for over two hundred years. The common practice at this time was to choose descriptive names based on physical characteristics. Colloquial speech referred to sharks as “sea dogs,” and carcharias comes from the Greek “Carcharos” (ragged), which Belon associated with the appearance of the shark’s teeth.

|

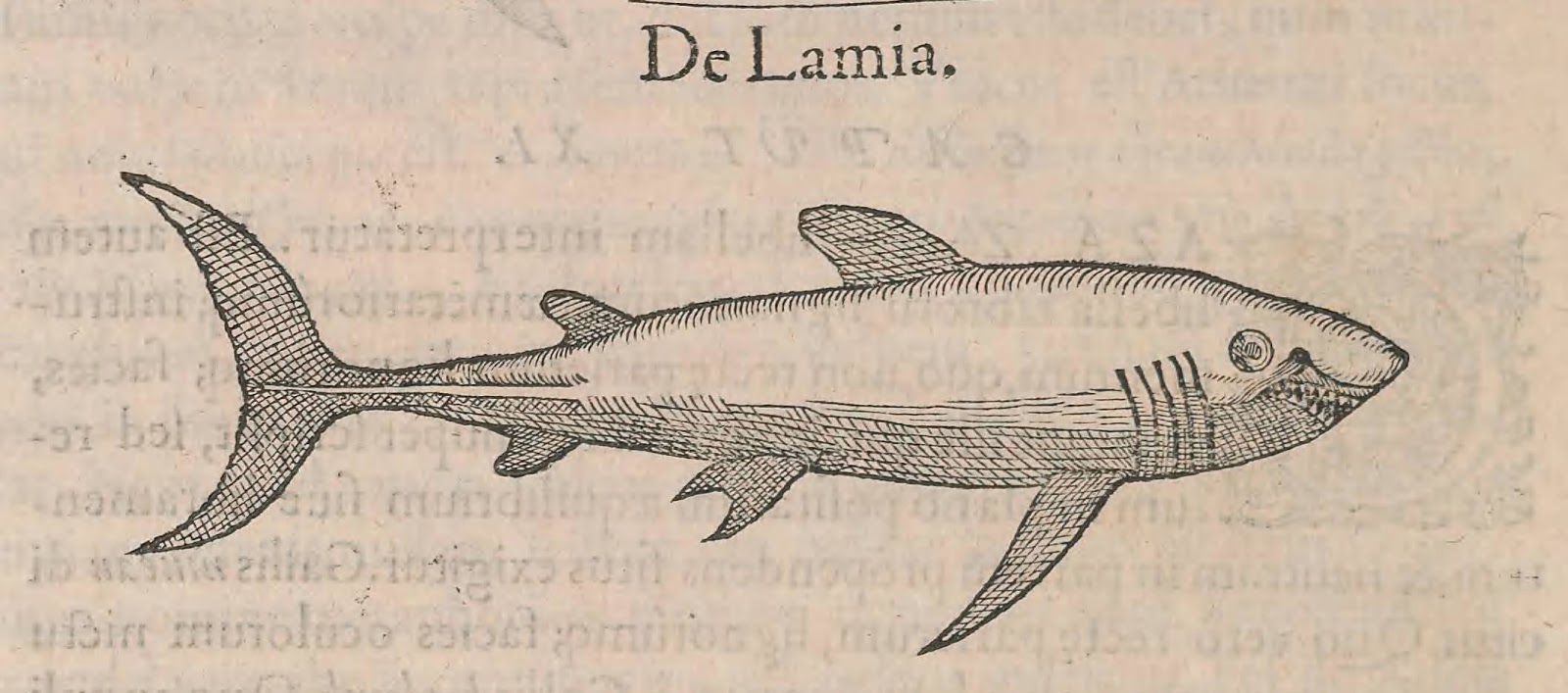

| De Lamia. Guillaume Rondelet. 1554. Libri de Piscibus. |

In 1554, French physician Guillaume Rondelet gave us another illustration of a Great White, under the name De Lamia (a child-eating demon in Greek mythology). Publishing Libri de Piscibus Marinis, Rondelet described more than 440 species of aquatic animals. Along with his illustration, Rondelet conveyed a tale of one specimen found with a full suit of armor in its belly. He also proposed that it was this fish, and not a whale, that was the culprit behind Jonah’s Biblical plight. A whale, he postulated, did not have a throat wide enough to swallow a man whole and regurgitate him later.

|

| Hammerhead and Catsharks. Ippolito Salviani. 1554. Aquatilium Animalium Historiae. |

That same year, Ippolito Salviani published another book on fish, Aquatilium Animalium Historiae, replete with engravings that included the hammerhead and (most likely) catsharks.

Though Conrad Gessner may have published accounts of many mythical beasts (such as the Ziphius in 1560), his 1558 work Historia Animalium (2nd edition linked here) was an attempt to give a factual representation of the known world of natural history. Within it, he included a much more recognizable illustration of the Great White (under both names Lamia and Canis carcharias). The study was based on a dried specimen, thus accounting for the rather desiccated appearance.

|

| Gessner’s Lamia. Conrad Gessner. 1604. Historia Animalium (2nd edition). |

Finally, in 1569, the word “Sharke” finally finds its place in the English language, popularized by Sir John Hawkins’ sailors, who brought home a shark specimen that was exhibited in London that year.

Influenced by the violent, and commonly exaggerated, stories circulated by sailors and explorers, general perception pegged sharks as ravenous beasts intent on devouring everything in sight.

Sharks and the “Modern” Era

By the 1600s, a more widespread attempt to classify fish according to form and habitat, and a fresh curiosity in shark research and diversity, found a footing in scientific research.

In 1616, Italian botanist Fabio Colonna published an article, De glossopetris dissertatio, in which he postulated that the mystical glossopetrae were actually fossilized shark teeth. The article had little impact, but in 1667, following the dissection of a Great White shark head, Danish naturalist Niels Stensen (aka Steno) published a comparative study of shark teeth, theorizing for the first time that fossils are the remains of living animals and again suggesting that glossopetrae were indeed fossilized shark teeth.

In the mid-1700s, a famous figure emerged. In 1735, Swedish botanist and physician Carl Linnaeus published his first version of Systema Naturae, at a mere 11 pages. Within this first edition, he classified sharks in the group Condropterygii, along with lampreys and sturgeon.

Linnaeus continued expanding his classification system, and in 1758 he published the tenth edition of Systema Naturae – the work we consider the beginning of zoological nomenclature. Within this edition, Linnaeus introduced binomial nomenclature, a naming scheme which identifies organisms by genus and species, with an attempt to reflect ranked hierarchies. This system provides the foundation of modern biological nomenclature, which groups organisms by inferred evolutionary relatedness.

|

| Squalus carcharias. Carl Linnaeus. 1758. Systema Naturae (10th ed.). |

Within Systema Naturae (10th ed.), Linnaeus identified 14 shark species, all of which he placed in the genus Squalus, which today is reserved only for typical spurdogs. He also presents his binomial for the Great White: Squalus carcharias. And he, like Rondelet before him, suggests that it was indeed a Great White that swallowed Jonah whole in ancient times.

|

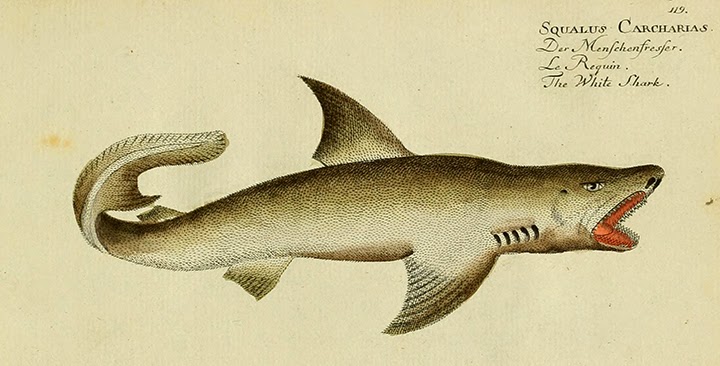

| Squalus carcharias. Marcus Bloch. 1796. Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische. |

By the late 1700s, we see a greater attempt to distinguish between the varieties of white sharks. From 1783-1795, Marcus Elieser Bloch published twelve volumes on fish under the title Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische, with 216 illustrations. His Great White, perhaps the first in color, bears Linnaeus’ name. And in 1788, French naturalist Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre gave the porbeagle shark its first scientific name, Squalus nasus, distinguishing another “white shark” as a distinct species.

|

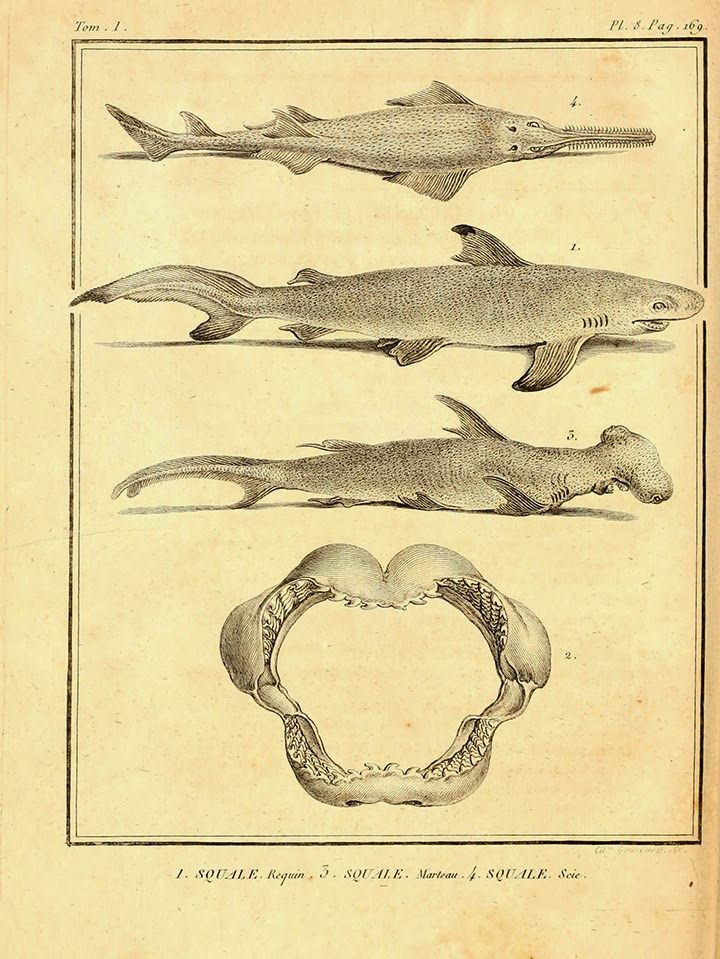

| Squalus. Bernard Germain de La Cepede. 1798. Histoire Naturelle des Poissons. |

French zoologist Bernard Germain de La Cepede grouped sharks, rays, and chimaeras as “cartilaginous fish,” identifying 32 types, in his 1798 work Histoire Naturelle des Poissons. He describes the “white shark” as the largest shark (a distinction truly held by the whale shark).

|

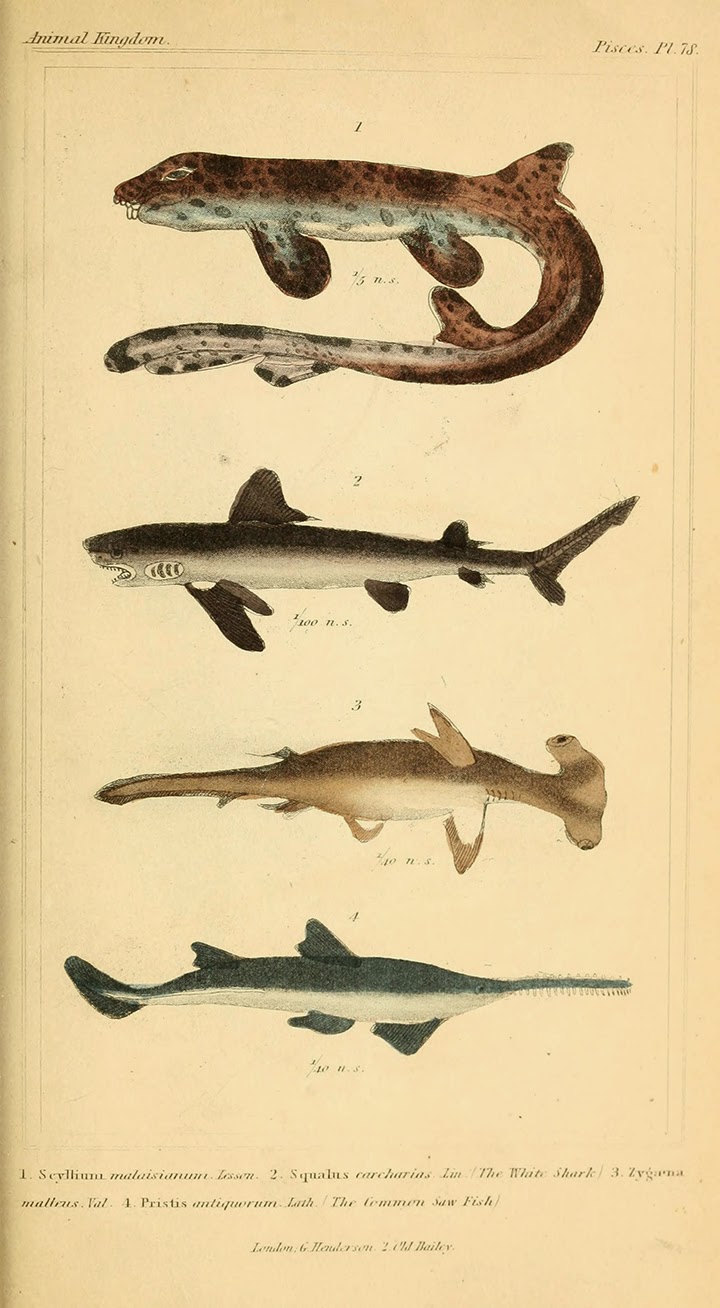

| Selachians. Georges Cuvier. The Animal Kingdom (1837 ed.). |

In his 1817 work The Animal Kingdom, French anatomist Georges Cuvier listed sharks as “selachians,” a term still in use today as the clade including sharks: Selachimorpha.

In 1838 we see the first use of the modern Great White genus name. Scottish physician and zoologist Andrew Smith proposed the generic name Carcharodon in a work by Johannes Müller and Fredrich Henle (linked here in Smith’s later 1840s publication), pulling together the Greek “carcharos” (meaning ragged and used in the association by Belon nearly 300 years earlier) and “odon” (Greek for “tooth”). Thus, Smith was proposing a name meaning “ragged tooth.”

Finally, in 1878, Smith’s genus name “Carcharodon,” and Linnaeus’ species name “carcharias” were pulled together to form the scientific name we know the Great White by today: Carcharodon carcharias.

Thanks to the dedication and curiosity of past naturalists and contemporary taxonomists, we’re now aware of the incredible diversity of sharks. There are over 470 species known today; that’s quite a leap from the mere 14 species identified by Linnaeus over 250 years ago!

Want more Shark content? Get over 350 free shark illustrations in the BHL Flickr collection, and browse dozens of historic books on sharks in our BHL and iTunes U collections. You can also explore the incredible diversity of sharks in the Ocean Portal.

Happy Shark Week!

Leave a Comment