Garden Stories: A Celebration of Gardening

Friday, March 20, 2015, we celebrated the March equinox (and, incidentally, a total solar eclipse!), when the sun appears to cross the celestial equator heading northward. In the northern hemisphere, this is also known as the vernal equinox. For those in the southern hemisphere, it means that autumn is upon them, and cold days are ahead. But for those of us in the northern hemisphere, it means that Spring is officially here!

The coming of spring is therapeutic for many – a time for new life, a break from the grayness of winter, and a signal to get the trowels, shovels, and gardening gloves out. Many hopeful gardeners have poured over their fall and winter seed catalogs for months, fantasizing about the colorful Edens they will nurture come springtime.

But did you ever wonder about the history of the home garden, or even agriculture for that matter, and just when and how those beloved seed catalogs came about? What did gardens 100 years ago look like? What tools, fertilizer, and seed and plant varieties were available in the nineteenth, eighteenth, or even seventeenth centuries? When did recreational gardening come into its own, and who were the men and women who helped make it happen?

A Walk Down the Gardening Memory Lane

Though speculative due to lack of written records, many researchers believe that Neolithic agriculture began several thousand years ago with attempts by hunter-gatherers to manage nature for their benefit, eventually resulting in the “Domestication Revolution” with the emergence of propagation, whereby ancient civilizations began distributing, dividing, and planting seeds and tubers [1].

For many millennia, most agriculture was undertaken strictly as a means to produce food to feed families and local populations or grow herbs for medicinal purposes. The flames of change began to ignite in Europe in the seventeenth century, however, with the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution, which resulted in an increased desire to understand the natural world and apply scientific methods to study it. Scientific advances in turn nurtured an agricultural revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whereby farmers applied new techniques to produce more crops across increased land areas, resulting in more food security and leisure time[1].

|

| Flowers in the Willibaldsburg fortress castle garden in Eichstatt, Germany. The book Hortus Eystettensis, commissioned by Prince-Bishop Johann Conrad von Gemmingen, illustrates the plants gathered together in the castle gardens. The garden and this book represent the first time in Western history that plants were being collected and celebrated not for their use but for their beauty and inherent interest. Hortus Eystettensis (1613). Volume One and Volume Two digitized by Biblioteca Digital del Real Jardin Botanico de Madrid. |

The rise of capitalism and growing populations fueled the development of commercial agriculture, and farmers (especially gentry farmers) started sharing and publishing their knowledge and botanical gardens began cataloging their seeds and producing seed lists (which included many plant species new to science), articulating the seeds housed at the garden available for international exchange with other institutions. As a result, agriculture not only became more prominent, but citizens (particularly those in urban environments) began nurturing home gardens as leisure activities.

As commercialism increased and imperial expansion enabled the introduction of new plant species from expanded locales, a bustling seed trade developed, first in Europe and Western Asia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but quickly strengthening in America following the Revolution. American nurseries emerged as early as the seventeenth century, and David Landreth founded the first seed house in America in 1784 in Philadelphia.

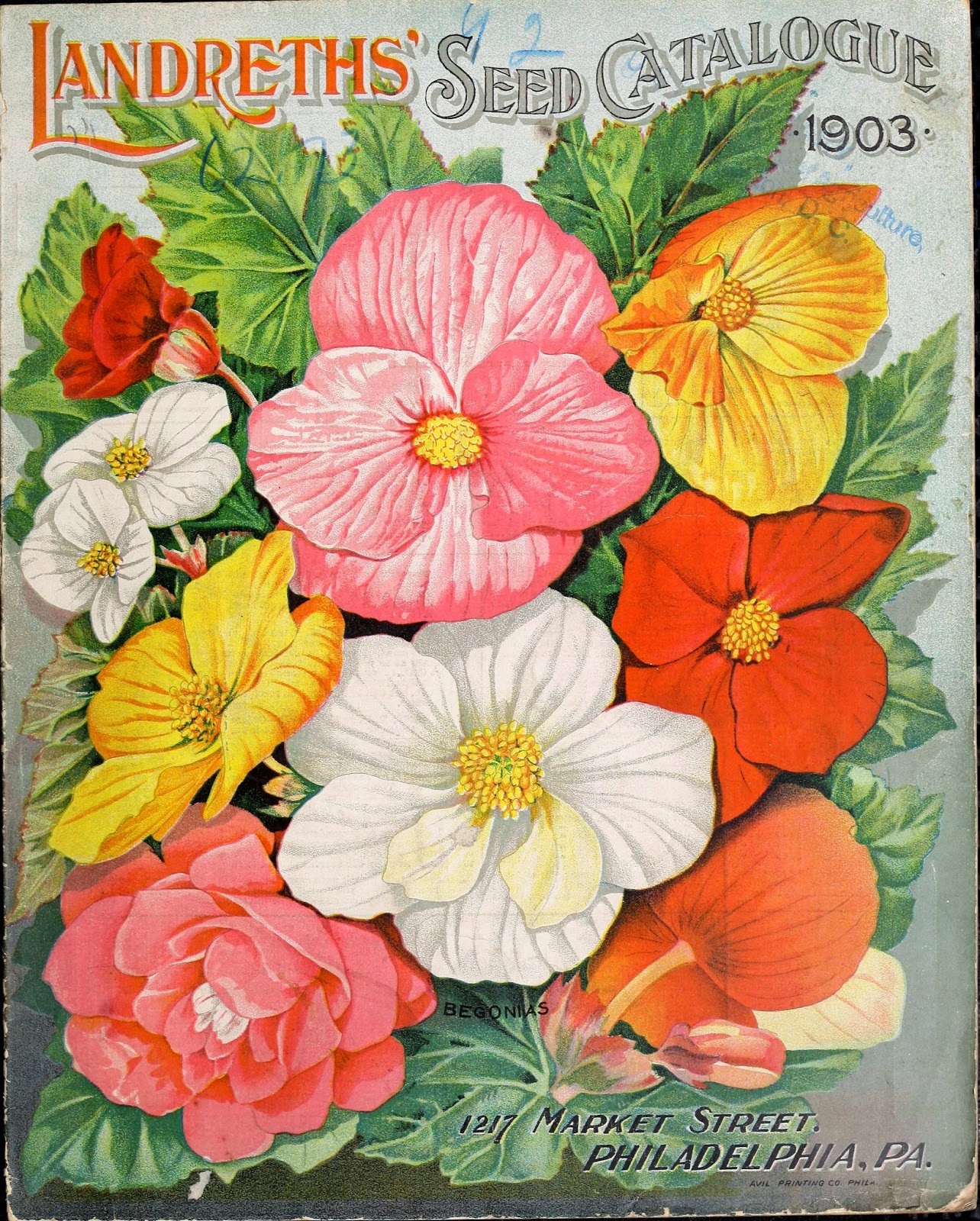

|

| David Landreth founded the oldest seed house in the U.S. in 1784 in Philadelphia. Landreth’s Seed Catalog: 1903. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/46368234. Digitized by the USDA National Agricultural Library. |

Rise of the Seed and Nursery Catalog

One of the most important innovations in the seed industry was the seed catalog, which offered a list of seeds and bulbs, and later garden tools and supplies like fertilizer and insecticides, for sale from the issuing company.

In the late 1500s, kings and wealthy aristocrats began having their exotic plant collections cataloged within elaborately-illustrated books called florilegia. Emanuel Sweerts‘ 1612 Florilegium, rather than being simply a catalog of his collection, presented a list of plants he could offer for sale, making it the oldest-surviving European plant catalog [2].

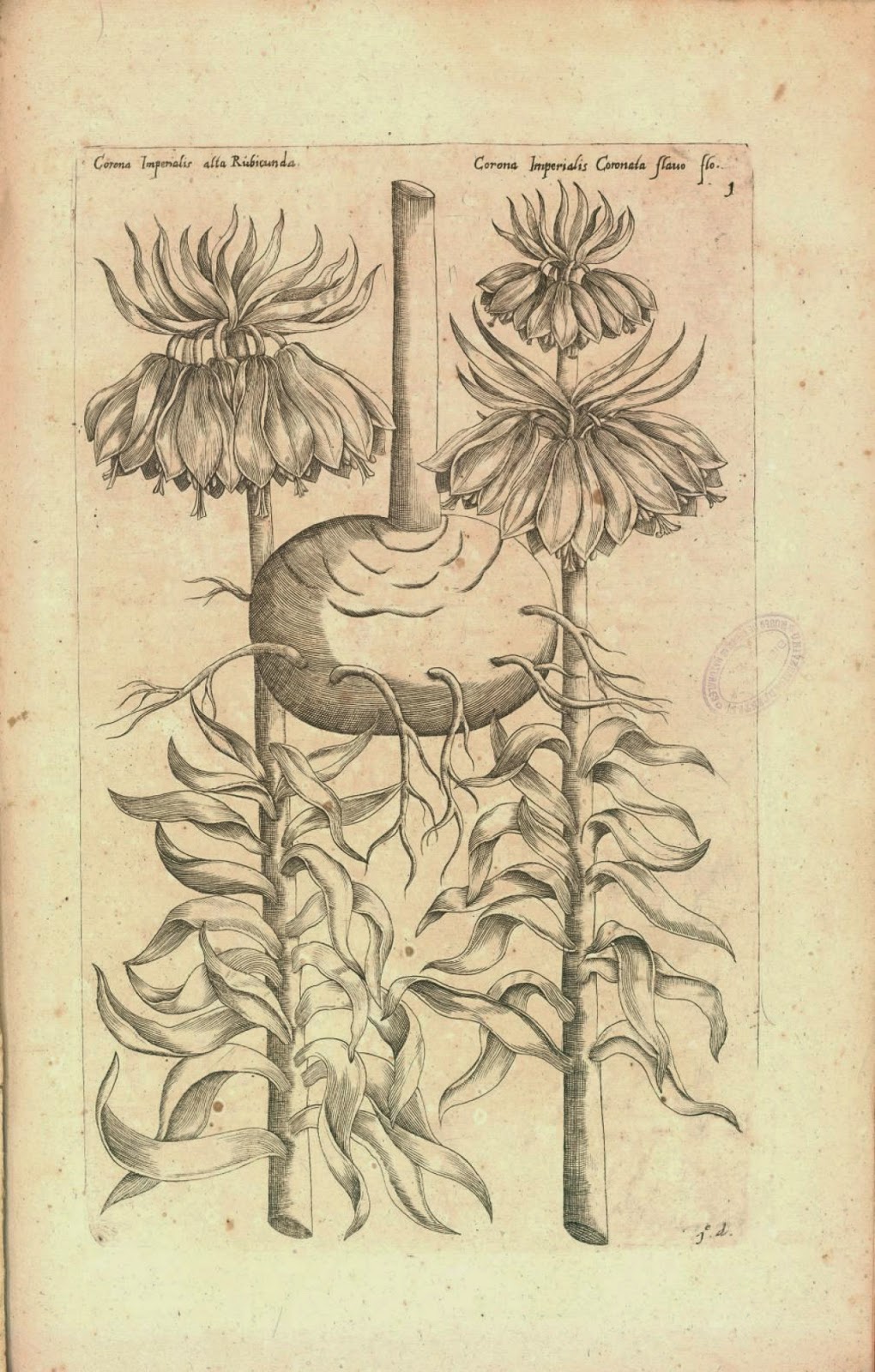

|

| Fritillaria imperialis in Sweerts’ 1647 Florilegium amplissimum et selectissimum. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/75687. Digitized by Biblioteca Digital del Real Jardin Botanico de Madrid. |

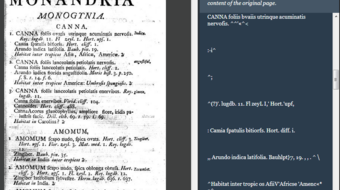

In 1688, the first nursery catalog was published in Europe [3]. Early catalogs were simply listings of seeds or plants for sale, often articulated by Latin names and frequently in broadside form, lacking ornamentation, illustrations, or even prices. One of America’s first nursery catalogs was a broadside published in 1783 by John Bartram Jr [4]. Early nineteenth century seed advertising also consisted of short notices of seeds and tools for sale in gardening publications, very much in the newspaper “classifieds” style [5].

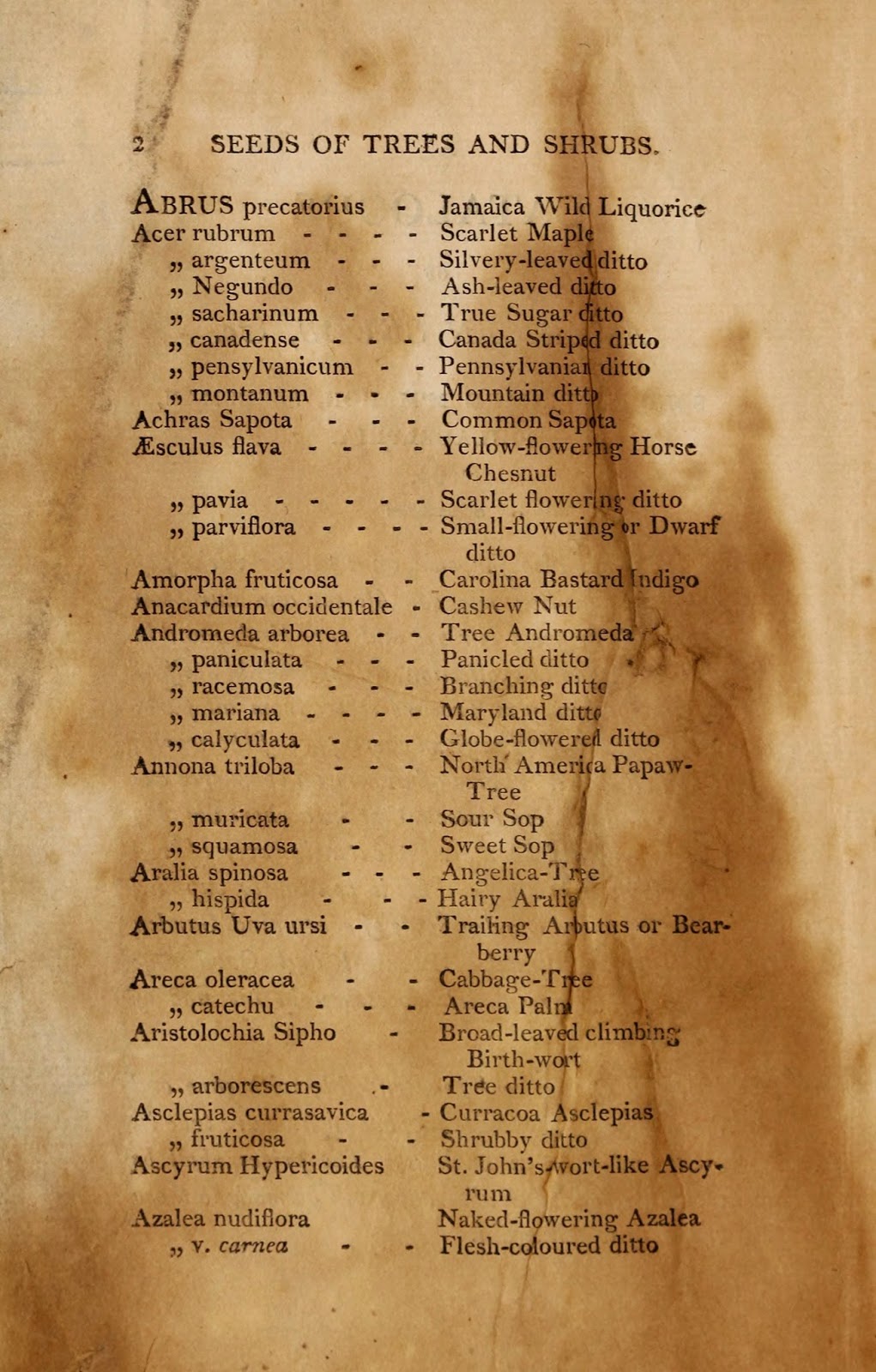

|

| Tree and shrubs seeds offered for sale in the first American seed catalog in booklet form. M’Mahon, Bernard. A Catalog of American Seeds. 1804. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/44425432. Digitized by the USDA National Agricultural Library. |

In 1804, the first American seed catalog in booklet form was published by Bernard M’Mahon, and by the 1820s in America, simple illustrations appeared in select catalogs [6]. Throughout the nineteenth century, horticultural manuals became increasingly popular, with growing instructions expanding to inclusion in catalogs as the industry bloomed, with the Shakers being early adopters of such practices (incidentally, the Shakers were also the first to popularize the use of seed packets) [7]. The seed catalog became an increasingly important component of the seed business in the middle of the nineteenth century. Nurseries began publishing regular annual catalogs in the 1840s, which were mailed, often at great expense, to various segments of a merchant’s customer base. Expanding transportation networks, the growth of the US Postal Service, and a new Post Office classification system in 1863 assigning low rates to instructive periodicals and seeds, allowed the seed industry to flourish at an unprecedented scale through the mail order phenomenon. The mail order gardening business first centered on fruits and vegetables but grew to include flowers and especially ornamentals towards the last quarter of the nineteenth century [8].

|

| The Fruits of America (1848-56) by Charles Hovey is the first major American book with exclusively chromolithographed plates. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/20359525. |

Printing innovations in the mid-nineteenth century transformed seed catalogs into beautiful marketing tools that stimulated customer appetites with visual representations of an advertised-seed’s potential. The multi-colored printing process of chromolithography was patented by Franco-German lithographer Gottfried Engelmann in 1837 [9] and introduced to the U.S. by William Sharp in 1841. By 1851, the first major American book with exclusively chromolithographed plates, The Fruits of America by nurseryman Charles Hovey, was published [10]. By the 1860s, chromolithography appeared in seed catalogs, thanks in large part to innovative nurseryman James Vick. Benjamin K. Bliss, however, is credited by horticultural historian Ulysses P. Hedrick as the first to introduce color to the catalog in the US in 1853. According to Elizabeth S. Eustis in “The Horticultural Enterprise: Markets, Mail, and Media in Nineteenth Century America,” Bliss’ 1867 “autumn catalog featured the earliest example so far discovered of chromolithography as the color process in a horticultural catalog” [11]. By 1890, commercial use of photographs in magazines and newspapers began, with, according to Ernest Morrison in J. Horace McFarland: A Thorn for Beauty, J. Horace McFarland being the first to use halftone images in horticultural publications [12].

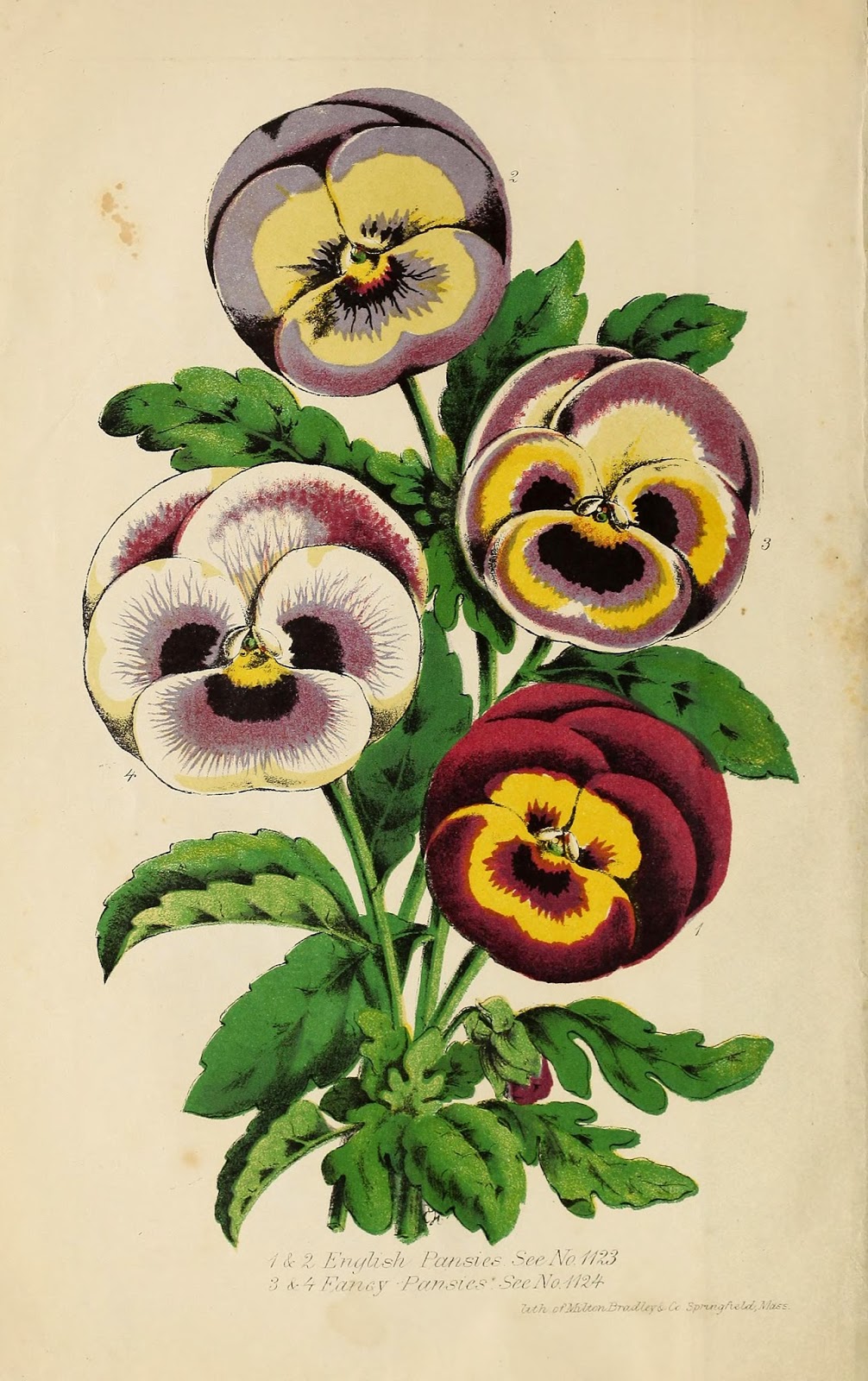

|

| B.K.Bliss is credited as the first to introduce color to the seed catalog in 1853. B.K. Bliss and Son’s illustrated spring catalogue and amateur’s guide to the flower and kitchen garden. 1870. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/44492905. Digitized by the USDA National Agricultural Library. |

Increased competition and growing costumer demands for novelties led to the popularity of hybrids (offspring produced by breeding two genetically distinct plants) in the nineteenth century, with certain varieties offered only through certain companies and beautifully portrayed in seed catalogs [13]. By the end of the nineteenth century, women had also entered the seed and flower business, including Carrie H. Lippincott, who established the first seed company in the U.S. to be founded and managed by a woman [14].

|

| Hybrid Lilac, The Klager Lilac. Cooley’s Gardens. 1931 fall catalogue of new hybrid lilacs and Japanese irises. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/44394461. Digitized by the USDA National Agricultural Library. |

Seed Catalogs: More than Horticultural Novelties

While they stimulate our gardening imagination, help us trace the development of the seed industry, and offer insight into the plant varieties offered to consumers throughout the centuries, seed catalogs are also important reflections of social and cultural values over time, changing agricultural and printing technologies, evolution of garden fashion and landscape design, and the development of botanical science. For instance:

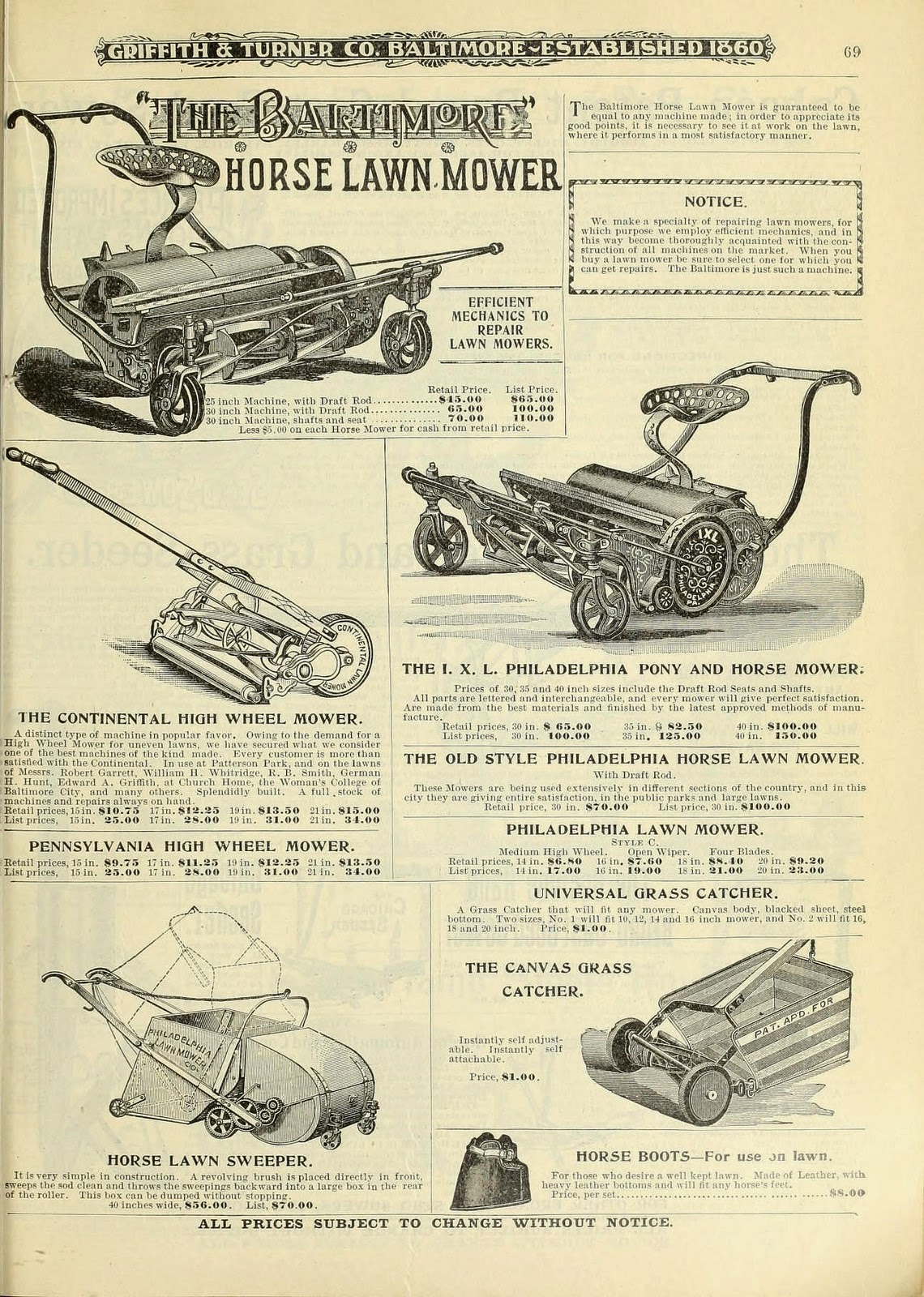

- Seed catalogs show changes in gardening technology and tools over time. This 1906 catalog lists 29 tools for sale. By the 1860s, catalogs listed dozens of specialty tools for specific tasks, like grass shears, wooding shears, ladies shears, and hedge shears. This 1900 catalog proudly displays “Iron Age” garden and farm implements. The lawnmower, first invented by Edwin Budding in England in 1830, began being popularly manufactured starting in the 1860s, and in 1902 Ransomes produced the first gasoline-powered lawnmower. By 1900 various models were selling for between $6-$100 retail.

|

| Various lawnmower models for sale in 1900. Farm and garden supplies : Griffith and Turner Co. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/43837949. Digitized by the USDA National Agricultural Library. |

- Pest control is a major business today. Seed catalogs help us trace the development and introduction of pesticides and fungicides. Compare the offerings from 1881, 1893, 1907, and 1934, for example.

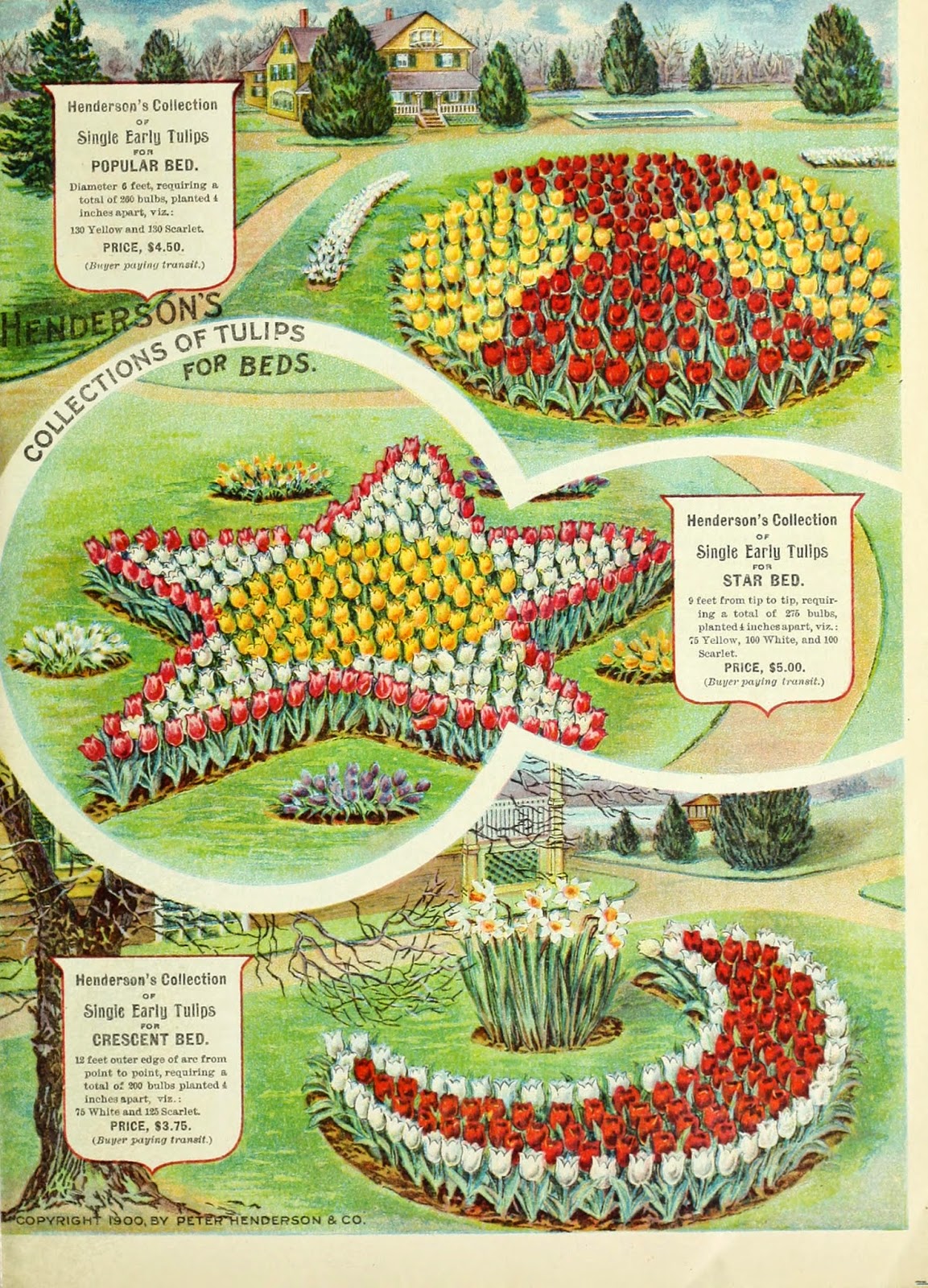

- Seed catalogs help us trace changes in garden plant popularity and landscape design over time. For instance, from 1865-1900, “bedding out,” which involved laying out patterns on the ground and filling them in with colorful plants, was all the rage. After the turn of the 20th century, bedding out was replaced by cottage gardening, which uses informal design and traditional materials. Check out the awesome tulip bed patterns in this 1900 catalog.

|

| “Bedding Out” Garden Style. Peter Henderson and Co. Autumn bulbs catalogue : 1900. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/43899723. Digitized by the USDA National Agricultural Library. |

Garden Stories: A Week Long Event for Garden Lovers

All this week, we’ll be exploring the fascinating world of gardening, including garden history topics such as the development of hybrids, heirloom gardening, women in the seed industry, revolutions in garden marketing through art, and the vital role the Shakers played in the American seed industry. Follow our blog for more great stories! We’ll also be sharing great gardening tips and plant factoids with help from our BHL members and affiliates. And we’ll be using the over 14,000 seed and nursery catalogs in BHL to help tell these stories. Join in all the gardening fun by:

- Following our blog and #BHLinbloom on Twitter and Facebook (or go directly to BHL’s Twitter and Facebook) this week.

- Browsing over 2,500 seed and nursery catalog images in our Flickr collection.

- Exploring select seed catalog art, and stunning bookmarks and postcards developed by Cornell Library, on Pinterest.

- Seeing garden history come to life on the Smithsonian Libraries’ Tumblr.

- Purchasing your very own Garden Stories T-Shirt through T-Fund. All proceeds will go to help us digitize more pages for BHL. Our goal is to sell enough shirts to digitized 5,000 pages. Can you help us get there?

|

| Garden Stories T-Shirt available through TFund. |

More Great Gardening Resources from our Partners

Can’t get enough gardening fun? Explore these great resources from our partners:

- Cornell University Library Mail Order Gardens Exhibit

- Cornell University Gardening Guide

- Missouri Botanical Garden Help for the Home Gardener

- Natural History Museum, Los Angeles County Nature Garden

- The New York Botanical Garden Seed Catalog LibGuides

- The New York Botanical Garden Plant Information and Gardening Guide

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Nursery Catalogs and Seed Lists

- Smithsonian Libraries Seed and Nursery Catalogs Exhibit

- Spring Gardening Checklist via Smithsonian Gardens

- USDA National Agricultural Library Seed and Nursery Catalog Collection

- USDA The People’s Garden Video and Webinar Gardening Resources

- Find more online gardening resources, tips, and help on the BHL Gardening Resources Page.

References

- Kingsbury, Noel. Hybrid. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009, 1-36. Print.

- The Seed and Nursery Catalog in Europe and the U.S. “Earliest European Seed and Nurseru Catalogs.” Oregon State University Libraries. Web. February 2015. http://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/seed/earliest/earliest-european/.

- Kingsbury, Noel. Hybrid. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009, 75. Print.

- Christopher, Thomas. “Heirloom Seed Catalogs.” Horticulture. Dec.(1985): 25. Print.

- Kraft, Ken and Pat Kraft. “Seeds for Sale.” Country Living Gardener. 1.1(1993): 30. Print.

- Fraser, Susan M. and Vanessa Bezemer Sellers. Flora Illustrata. New York: New York Botanical Garden, 2014, 235. Print.

- Ibid., 236

- Ibid., 249

- Ferry, Kathryn. “Printing the Alhambra: Owen Jones and Chromolithography.” Architectural History. 46(2003): 175–188.

- Fraser, Susan M. and Vanessa Bezemer Sellers. Flora Illustrata. New York: New York Botanical Garden, 2014, 239. Print.

- Ibid., 251

- Morrison, Ernest. J. Horace McFarland: A Thorn for Beauty. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1995. Print.

- Kingsbury, Noel. Hybrid. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009, 139. Print.

- American Garden History. “Who was the mysterious feminist seed dealer and marketing genius Miss Carrie H. Lippincott?” Barbara Wells Sarudy, 2010-13. Web. February 2015. http://americangardenhistory.blogspot.com/2014/07/who-was-mysterious-feminist-seed-dealer.html.

Hi, friend!

This is very informative post. Thanks for sharing your great job!

I have read your post and learned a lot about A Celebration of Gardening. Obviously this is very good job.

Please, continue your good job in the future!

Thanks