Marjorie Eileen Doris Courtenay-Latimer: Beyond the Coelacanth

A version of this post was originally published on the blog of the Margaret Smith Library, SAIAB. It is reproduced with permission from the author, Sally Schramm.

Willie and I look forward to our first born towards the end of April/beginning of May and we both pray it will be a lover of all that is beautiful in nature. Willie wants it to be a botanist — I want it to be a lover of birds and animals.

Eric Latimer’s diary, 25th November 1906

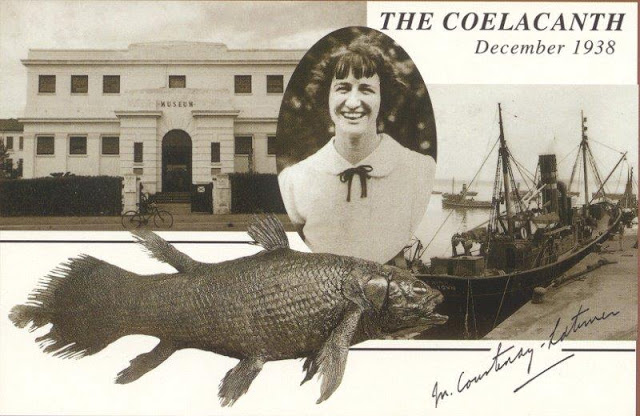

Marjorie Eileen Doris Courtenay-Latimer (1907-2004) is ubiquitously remembered and celebrated for her part in recognising that the large fish trawled by Capt. Hendrik Goosen and the crew of the Nerine in December 1938 was an astonishing find. This was to be identified as the first live coelacanth known to Western science. JLB Smith, the ichthyologist who first described it, named it Latimeria chalumnae after Marjorie, and the Eastern Cape river mouth near which it was found.

Reading the Border Historical Society’s The Coelacanth journal Commemorative edition in honour of Dr Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer (2004) we find a life dedicated to a great deal more than that single event. Her contributions to the Eastern Cape town of East London, and to the Museum in particular, were immense.

Born two months prematurely, surviving practically every childhood disease known — and the Flu Pandemic (1918-1920) — the apparently frail Marjorie’s interest in “all that is beautiful in nature” intensified as her family followed father Eric Latimer to his postings at a succession of often isolated railway stations in the Free State and Eastern Cape. The entire family walked and picnicked, collected, recorded and illustrated specimens, thoroughly appreciative of the wild areas around them.

Keeping natural history journals and scrapbooks became a life-long habit for Marjorie. Here we read in 1938, “Every where everything was beautiful — watched, talked and breathed nature. Every scrap of this day was heavenly”.

We also read of Marjorie, aged 24, as the first curator in 1931 (at £2 a month, with a petty cash allowance of 5/-) of the new and sparsely provisioned East London Museum, with its meagre collections; setting up displays (initially from her family’s own collections) and dioramas; her dedication in building collections both cultural and of natural history; her awareness of the museum’s value and interest to the public and especially to children; and of the planting of the indigenous museum garden. All this was accomplished in the early years with very little help; we read only of one named assistant Enoch [Enoch Elias], who helped Marjorie lug the coelacanth back to the Museum in 1938.

Other contributions tell of her stint on Bird Island in Algoa Bay for six weeks in 1936, with her parents as chaperones (mother enthused, father dreadfully bored); of her botanical and fossil-collecting field trips, often with close friends, specifically of the excavation and mounting of the almost-complete dicnodoni skeleton Kannemeyeria simocephalus.

Marjorie recounts many of these events from her early life and career, and explains how they ultimately contributed to the coelacanth “discovery”, in a 1979 paper published in the Occasional papers of the California Academy of Sciences. For example, it was because of her employment at the East London Museum that she met JLB Smith, with whom she developed a professional relationship that she called upon following her discovery in December 1938. And it was during her time on Bird Island that she met Capt. Hendrik Goosen, who became a regular source of specimens for her collecting activities for the Museum — and ultimately the supplied the famed coelacanth specimen.

Marjorie summarizes her story and the events that culminated in her famed discovery as such:

“This story is one of the most astounding records of a woman’s intuition, for:

had I never gone to Bird Island;

had I never met Dr. JLB Smith who, of all the scientists I met as a young girl struggling with meagre funds in a small Museum, always gave encouragement and never criticism;

and had I not gone to the wharf to wish the men a Happy Christmas,

there never would have been a coelacanth discovery in South Africa, on 22 December 1938.”

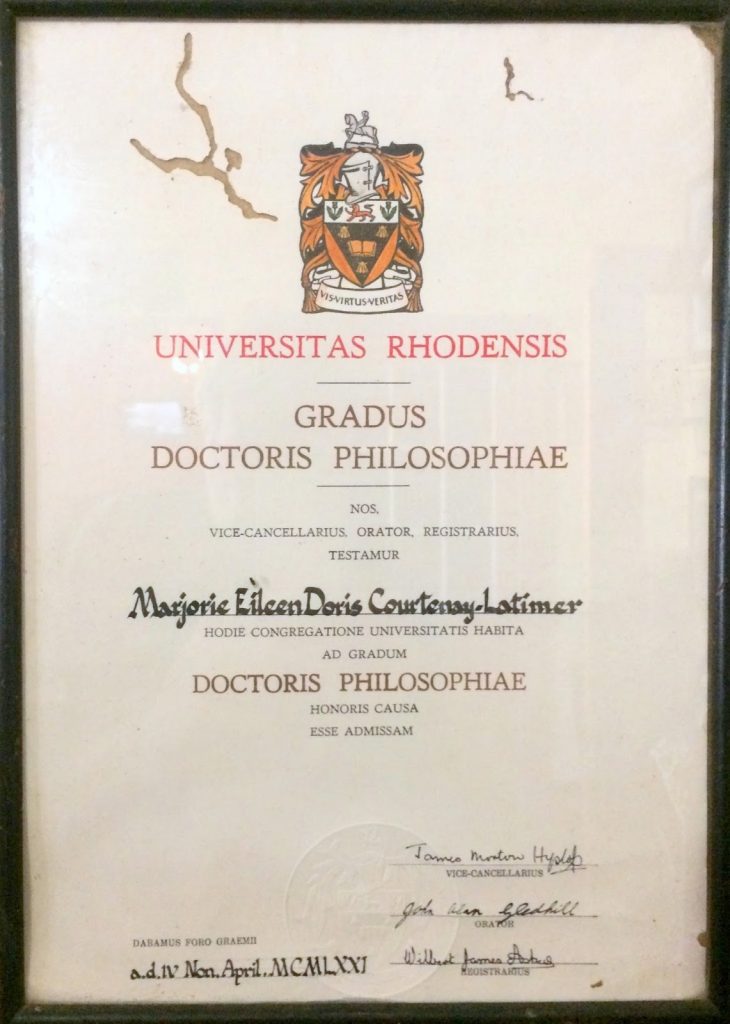

Marjorie was an author of scientific and popular literature on a wide variety of topics and was an active member of diverse museum, historical and natural history societies. She supported conservation and the establishment of nature reserves such as Potters Pass, East London, and Gonubie Nature Reserve. Finally, we read of her numerous civic awards, honorary fellowships, and her Honorary Doctorate from Rhodes University.

On her retirement as Director from the East London Museum in 1973, Marjorie moved to Witselbos in the Tsitsikamma area. Her house Mygene was named for her childhood nickname “Genie”, from the popular song “Jeanie with the light brown hair”, “… I see her tripping where the bright streams play, Happy as the daisies that dance on her way …”

Having done a brick-laying course at the East London Technical College, she tackled a kitchen extension with aplomb. She painted and sculpted in clay. She still kept in touch with friends and colleagues world-wide. Forays into nature continued as ever.

She returned to East London in the 1980s. On her moving to frail-care shortly before her death in 2004, a collection of Marjorie’s personal effects (including the certificate and house plaque above) were left behind in the house which she had recently occupied.

Fortuitously, these were subsequently recovered when the house was sold ten years later. A serendipitous chain of events led to the display of some items at Thomas River Historical Village near Cathcart, Eastern Cape. The Village is the site of the original Thomas River Station — where Eric Latimer and his family had lived in the late 1920s.

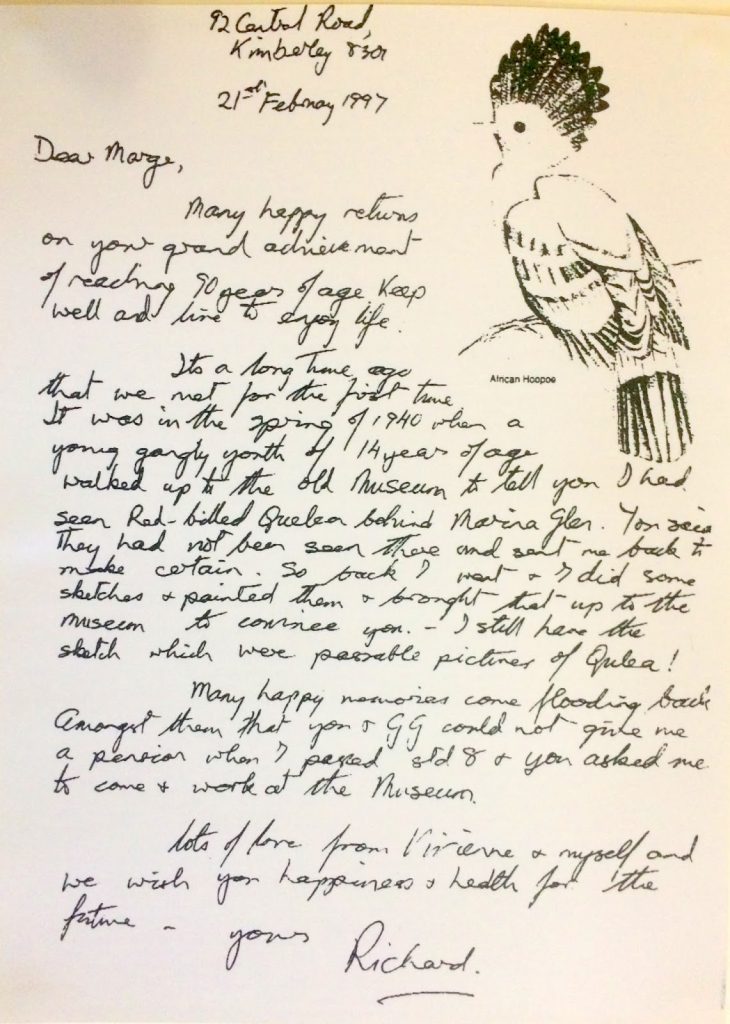

Among the treasures found was the album presented to Marjorie on her 90th birthday in 1997 “with appreciation and admiration” by the South African Museums Association. There is a facsimile copy at Thomas River Historical Village. Many of the contributors are a who’s who of prominent naturalists, authors and artists, all friends and colleagues.

Contribution by Richard Liversidge, ornithologist, previously Director, McGregor Museum, Kimberley. Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer Collection,Thomas River Historical Village. (Pic: Mike Schramm)

The many happy memories recalled through the warm contributions would have delighted Willie and Eric Latimer. Their first child was a daughter who truly was a “lover of all that is beautiful in nature”.

Marjorie Courtney-Latimer — a life lived richly beyond the coelacanth!

What a wonderful story. One of my inspirations – a remarkable woman.